It’s difficult for supply chain professionals to comprehend, but most of their colleagues couldn’t care less about fill rates or asset utilization.

For that reason, supply chain management in most companies is considered to be everything - except sexy.

Supply chain managers who outline their must-win battles regularly point to initiatives like forecast improvement, master data standardization, ERP implementations, or warehouse optimization.

These battles are clearly crucial for boosting supply chain performance but, at the same time, they’re a hard sell to senior management.

That’s because the concepts and implementations are very technical, understanding interdependencies requires in-depth knowledge, and the actual benefits are difficult to judge.

Moreover, supply chain initiatives are competing for senior management’s attention among many other more accessible - and sexy - topics like market entries, potential acquisitions, or new product launches.

When asked for their biggest personal pains, supply chain leaders frequently mention the executive team’s limited interest in supply chain processes or the benefits they provide.

Even the hot topics of the day, like Big Data and reshoring, fail to raise the profile of supply chain teams, even though they have been working on these topics for many years.

Of course, there are examples of successful firms that have deeply embedded SCM into their DNA and include SCM topics in Board-level discussions. They understand that SCM - if positioned appropriately and executed correctly - can make the difference between mediocre and outstanding business performance.

After all, providing truly distinctive customer service or expanding into new markets is unthinkable without a world-class supply chain to support the chosen strategies. Likewise, inventory reduction is not simply a top-down target set by the financial organization; it takes a supply chain to hit those targets.

To make a true difference, the Board must understand SCM. For instance, strategic trade-offs, such as whether to focus on cost versus customer service, ultimately translate into supply chain requirements and targets.

Similarly, more tactical Board decisions, such as whether to approve an important deal that requires potentially risky decisions on securing components or supplier capacity, cannot be executed without support from SCM.

The supply chain team needs to create and evaluate the relevant scenarios on investments and flexibility, while the Board ultimately makes the final decision. On a more operational level, the Board needs to be aware of potential conflicts between sales and operations that demand answers if not solved at the lower levels of the organization.

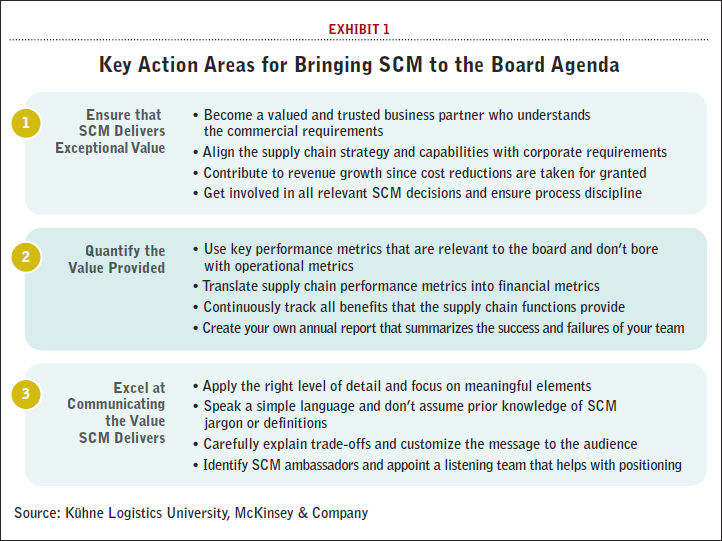

At far too many firms, however, senior management still asks the SCM team to simply reduce costs or blames them for missed shipment, late deliveries, and unhappy customers. What can supply chain leaders do to overcome these misperceptions and bring SCM to the Board’s agenda? To raise its profile, we have developed a framework with three key action areas that supply chain leaders should leverage to bring the topic to the Board agenda (see Exhibit 1).

First, supply chain leaders need to ensure that SCM is accepted as a trusted business partner in the company by delivering exceptional value. The function should go beyond classic cost reductions and enable revenue growth by introducing supply chain innovations. Therefore, the function needs to fully align supply chain capabilities with the overall needs of the business and become involved in strategic decision making.

Second, supply chain leaders must quantify the value that SCM provides in a relevant and coherent manner. Selecting appropriate KPIs that are understood by the Board and commercial counterparts is essential, just as tracking all the benefits for the department’s own annual report is now recognized as a best practice.

Third, supply chain leaders must speak the language of business. They need to communicate their value using terms and concepts that are accessible to everybody. In particular, using the right level of detail and explaining concepts and trade-offs to non-SCM experts will ultimately enhance the entire team’s understanding of the topic.

Common SCM Misperceptions

We often hear from SCM leaders that senior management and other departments don’t perceive supply chain’s contributions in the intended manner.

A SCM executive in the process industry recently stated that his team is “… perceived as a bunch of nerds who do complicated stuff that nobody understands. Even worse, colleagues feel that we never really deliver what is requested, and we ultimately get blamed for all of the things that go wrong.”

While this seems like a rather discouraging statement, we came across several very common and similar misperceptions regarding the position of supply chain functions in firms. In particular, employees with little prior exposure to operations often have a vague understanding of what SCM does.

Frequently, SCM is still confused with classic logistics operations that focus on storing and moving goods, like warehousing and transportation. The fact that many firms have outsourced a significant portion of their logistics operations to 3PLs often leaves a blank spot.

Other companies relabeled logistics functions and professionals as SCM without expanding their operational responsibilities - it’s still warehousing and transportation under another name. However, SCM’s scope has evolved significantly, and now includes the responsibility of managing the end-to-end value chain.

The confusion with logistics also triggers an overemphasis on reducing costs. C-level executives often associate logistics with the increasing commoditization of transportation and warehousing activities. Thus, all efforts are focused on cost cutting and containment. Little room is left for innovative activities that could provide significant value at a marginally higher cost.

An additional challenge is the high complexity of many supply chain decisions, which cannot be fully captured by outsiders; in particular, the operational and tactical decisions supply chain managers make to optimize production volumes, capacity allocations, and inventory levels are often incomprehensible to outsiders. Hence, SCM is frequently perceived as a black box that nobody can really follow.

Executives and managers in other functions are additionally confused by the technical jargon unique to the “dark art of supply chain management.” This is especially an issue if SCM does not provide the required quantities at the right time.

After all, supply chain news typically only makes the headlines when something goes wrong that affects the customer, such as BMW’s issues with spare parts deliveries due to IT issues or the Adidas group’s shrinking market share in Russia due to an inadequate distribution center.

The same is true within companies; in a world of zero defects and Six Sigma, customer fill rates of 95 percent don’t sound very impressive to commercial partners, even if the SCM team is leading a heroic effort to hit that number. Instead, the 5 percent that was not delivered on time and in full is neither understood nor accepted, and SCM takes the blame for alienated customers and lost revenues.

Ensure that SCM Delivers Exceptional Value

Moments of fame for supply chain executives are fleeting. Senior management generally doesn’t care about better end-to-end planning or new supply chain risk mitigation processes - they care about results that drive top line growth or improve the bottom line.

To advance to the next level, supply chain teams need to become trusted business partners who deliver exceptional value. Getting the basic fulfillment processes right is a fundamental prerequisite for sitting at the Board Room table. As the head of a big chemical business division emphasized: “I would love to involve my SCM folks in more decisions, but they don’t really know what the business needs.”

In fact, it often feels as if sales and supply chain live in two different worlds. Far too many key account and product managers have seen supply chain managers shake their heads about the aspirations for filling customer requests. In this case, those working in supply chain need to understand the true commercial requirements and build customer intimacy - at least with their internal customers.

One way to address this is to develop supply chain talent that is cross-functional by nature and understands the needs of other departments. Best practice companies foster this through job rotation programs that shuffle people between sales, finance, and operations. The gathered insights and developed network ultimately foster better involvement of the SCM team. Creditable talents often act as first points of contact within the organization regarding all supply-chain-related inquiries.

Once it has a better understanding of customer requirements, the supply chain team needs to align the supply chain strategy and capabilities with the corporate strategy. While managers on all levels are typically familiar with the corporate strategy, familiarity with the supply chain strategy is a different story, often because it is not well formulated or not aligned with the overall strategy.

We find a very close alignment between strategy and supply chain setup in best-practice companies where the supply chain team helps shape the strategic agenda. Cost leaders like IKEA, for instance, design their products for supply chain efficiency. Service leaders like Amazon implement technologies that enable a long tail and fast deliveries. Innovators like P&G execute excellent phase-in/out product life cycle processes. And integrators like Li & Fung carefully orchestrate a broad network of supplier and contract manufacturers.

To deploy a supply chain strategy that is in line with the company strategy, supply chain leaders must develop planning strategies and supply chain structures with a clear focus on true customer service and requirements.

Based on the strategy, the supply chain team needs to derive targets and identify the changes required to deliver the strategy and execute rigorously. Most important, the strategy should be concrete (too often, it is full of superfluous information), and communicated to the adjacent functions.

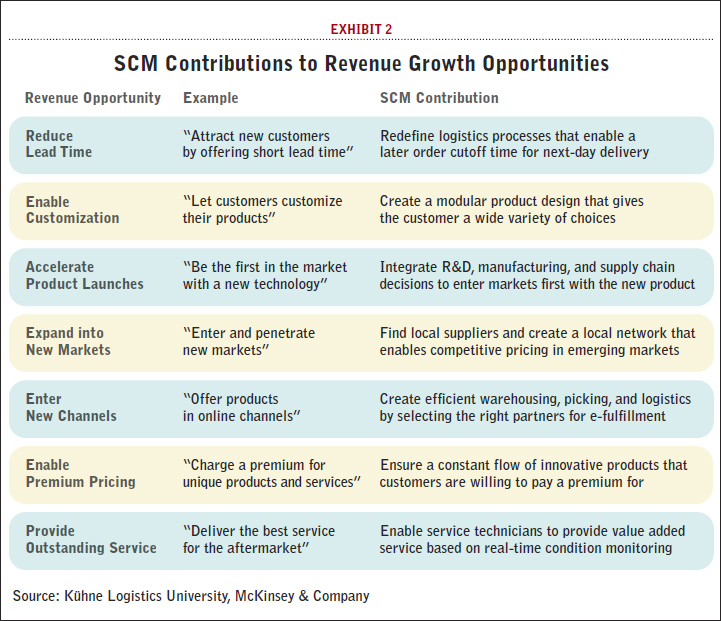

Clearly, supply chain managers need to be at the forefront of cost containment by additionally boosting process efficiency, leveraging more affordable suppliers, or introducing new technologies. However, a strong focus on cost can further marginalize SCM’s position in the company. High-impact supply chain teams provide additional value by enabling new revenue streams (see Exhibit 2).

By finding smart ways to customize products, enter new sales channels, or tap into new markets, these teams visibly support the top line and can argue for supply chain investments.

One example of this approach is a German market leader in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning that cleverly redesigned its spare parts fulfillment process. While the obvious choice was to re-engineer the process at a lower cost, the supply chain team opted for a different approach.

The new process enables customers to place their orders for next-day delivery later in the evening. This delivered a significant competitive advantage in a market where direct customers like plumbers or handymen can only order in the evening when they return from a job site.

Another successful example is a construction equipment manufacturer that offers its huge variety of products with a smart postponement strategy that enables significantly shorter lead times and has triggered double-digit revenue growth.

A final prerequisite for creating value is early involvement in all relevant SCM decisions. Clearly, this is partially a chicken-and-egg problem, but supply chain teams need to provide early input for many decisions. Other functions need to understand that many supply chain issues can be circumvented by a smart product design that enables fast supplier transitions, smaller packaging sizes, and more modularized components.

Likewise, promotions only thrive if raw materials, manufacturing, and logistics capacities are carefully planned, thus, minimizing stockouts while avoiding retailers’ forward buying. Similar to best practices in S&OP, the supply chain team should ensure that processes are well defined and that the involved functions enforce process discipline.

Quantify the Value Provided

If supply chain teams want a seat at the table, they must quantify the value they provide. We regularly ask supply chain leaders how they have shown their impact in the past year. Too often, their responses are either defensive or highly focused on operational metrics. There is no need to be defensive: If a team provides value, they should be proud to highlight it. However, to have impact, the message must be delivered in a language that is understood by the Board.

Take metrics. Top management certainly considers metrics that are based on strategic C-level objectives, such as EBIT, cash flow, new customers, or market share. Management pays little attention to operational metrics like pick rates, truck utilization, or inventory turns because it isn’t obvious how they affect the bottom line. To make SCM relevant for the Board, the reported supply chain metrics must be relevant - both from a company perspective and a financial perspective.

The link can easily be made by considering the strategic supply chain dimensions of cost, service, and capital. To be effective, however, these should be focused on the key metrics that drive the business, while the rest should stay within the supply chain team. No executive wants to see monthly reports with dozens of metrics that nobody understands.

In addition, it is helpful to link metrics with objectives and supporting initiatives. For example, the supply chain team of a fast moving consumer goods manufacturer has linked the customer orientation objective to the metrics of service level and customer satisfaction. The report also highlights supporting projects that aim to boost customer orientation through promotion management, customer management, and distribution processes, among others.

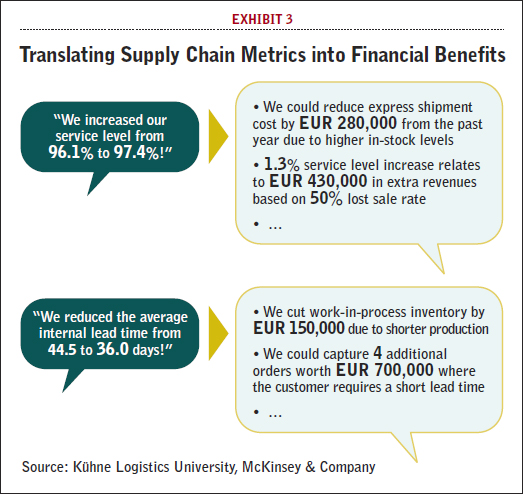

Translating supply chain performance metrics into financial metrics is the next vital step. Best practices include carefully developed KPI trees that gradually link operational metrics to financial metrics. Thus, potential shortcomings in supply chain metrics can be easily recognized. For example, many companies still use inventory turns as a key metric for measuring inventory performance.

However, when calculating the cash-to-cash cycle time (an important financial metric) from inventories, accounts payable, and accounts receivable, it is apparent that the stock range in inventory days is a much more straightforward metric. In addition, this metric is much easier to interpret for non-supply-chain experts.

If direct relationships between operational and financial metrics are difficult to justify, educated illustrations about the impact are helpful.

For example, service level is another abstract metric - however, collectively judging the benefits of service level improvements can help argue the case (see Exhibit 3).

The same is true for other even more intangible improvements like master data accuracy or real-time planning.

As a nice side effect, the quest for quantifying the benefits typically stimulates very fruitful and in-depth discussions within and across teams.

To provide evidence of the value that the supply chain has created, the team should continuously track all achieved benefits. Tracking needs to consider cost reductions, but it also should include revenues generated and costs avoided. In many companies, other departments are signing off on benefits to ensure plausibility.

Based on the gathered data, the supply chain team can create its own annual report, which highlights its successes and provides evidence for any further discussions. To ensure balance, the annual report should also have a section on failures like late product introduction or major orders lost, which highlights the lessons learned from these occurrences.

Excel at Communicating the Value SCM Delivers

Even if the supply chain team is doing a great a job, many supply chain leaders struggle to communicate their value. Supply chain departments rarely give themselves a mission that sticks. One exception is the German personal care company Beiersdorf, with its Blue Supply Chain Agenda: “We will deliver. Because we care.” Beiersdorf has gone so far as to say that “the Blue Agenda defines the course of our future.”

Beiersdorf, of course, does not define the rule. We have seen many frustrated supply chain managers in other companies who solved a vexing problem, only to see their commercial counterparts receive the kudos. The daily challenge of putting out fires like missed shipments and production breakdowns make it hard for supply chain managers to step back and paint the big picture that is critical for engaging the Board.

Often, supply chain managers don’t have the experience to communicate with senior management because there were previously too low in the hierarchy to have done so before. At the same time, supply chain managers love to tell their stories through numbers and Excel spreadsheets. A3-format Excel printouts and the details of an ingenuous new optimization algorithm rarely excite a senior manager.

Simplify, Simplify, Simplify

Common SCM challenges like S&OP, SKU rationalization, or inventory optimization are complex topics that are ill suited to a simple illustration. However, they demand a careful explanation - in particular to non-subject-matter experts.

All too often, we find that both the content and delivery of important messages end up confusing, irritating, and alienating to management and business partners. In particular, senior executives who have to deal with a myriad of issues often have only a few minutes to decide on important issues that require carefully customized messages. The inconvenient truth, as Albert Einstein states, is simple: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”

Great supply chain leaders understand the importance of a simple and focused message. They often test their team’s understanding with napkin contests or elevator talks: How well can the team concisely illustrate a specific problem or concept? We have all observed situations where sales has managed to secure an important customer order that requires rush deliveries from suppliers and the reshuffling of production schedules.

In these situations, supply chain executives need to communicate their requirements and challenges very precisely. In particular, supply chain investment projects need to be carefully explained if they are counterintuitive. For example, why should they invest in highly automated warehouses in certain cities while keeping manual, labor-intensive warehouses in other regions?

Too often, supply chain managers over emphasize complex and detailed topics. In all communications, it’s important to consider the knowledge base and experience of your counterpart to ensure that you don’t get lost in details or dwell on concepts that only supply chain insiders can follow. For example, the frozen horizon in production is often not at all frozen for others, and the understanding of service levels or forecast accuracies varies widely within the firm.

The guiding principle for the supply chain team is always to avoid unnecessary buzzwords or obscure acronyms. Not every manager is familiar with ASNs from suppliers, LTL shipments to customers, or ATP inventories based on the MPS. You might impress your SCM counterparts at the supplier or customer, but internal meetings suffer if different business functions don’t speak the same language.

Further complications commonly arise because other functions are not fully aware of the classic supply chain trade-offs between inventory, cost, and service. However, these trade-offs must be carefully illustrated and understood by all departments involved. What happens if we don’t fill a customer’s rush order? What is happening to the gross margin due to overtime and more expensive raw materials? What is the impact on other customers? Consistent service and supply policies that enable process discipline might be more profitable in the long run than constant fire fighting due to last-minute orders.

While supply chain managers are in a weak position when time critical decisions are made, a carefully prepared post hoc analysis that outlines the impact of the decision within the firm could be an eye opener for the future.

Consistent service and supply policies that enable process discipline might be more profitable in the long run than constant fire fighting due to last-minute orders. In other situations, carefully prepared analyses need to be conducted much earlier to avoid costly decisions. For example, a trade-off in product design might be the right call if reliance on an overseas supplier could trigger long lead times or high inventory levels.

The best companies invest in programs that create a company-wide awareness of the role of SCM in the organization. We have seen a variety of best practices. For example, some supply chain teams set up dedicated intranet sites to increase creditability and ensure that messages stick. Materials on these sites should be customized to inform a wider audience about relevant projects and practices.

Some firms also use more interactive material. Unilever, for instance, highlights the role of the supply chain by using the rich picture of a restaurant with pantry, kitchen, and table allocation. Other activities include specific supply chain trainings for non-supply-chain staff, which promote a general understanding of SCM.

To help break the silos and overcome internal challenges, the supply chain team may identify formal SCM ambassadors and appoint a listening team. Ambassadors could be managers from other functions with relevant supply chain knowledge gained from their prior careers or those who have a particular interest in SCM.

These ambassadors can spur ideas and help promote a joint understanding of the key processes and supply chain requirements in their functions. In particular, supply chain leaders who are new to a company should identify these valuable assets, which can aid in finding the right positioning for SCM in the company. Listening posts are less active but should also be consulted.

Messages that Stick

Without question, supply chain leaders add value to a company.

However, in order to earn a strategic role with senior management and the Board, SCM must improve its image within the organization.

To do so, supply chain leaders need to ensure that their message sticks.

First, they need to understand their position within the company.

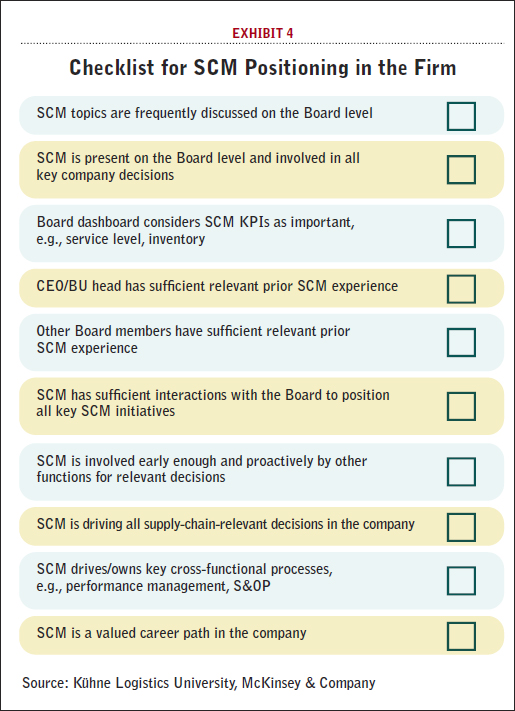

Exhibit 4 provides a checklist to identify the status quo.

Next, supply chain teams have to overcome certain misperceptions or confusions that might exist about the function.

We have outlined how SCM needs to think and act as a business partner in order to deliver value, quantify this value, and excel in communicating about the value.

In the end, supply chain leaders must successfully interact with the other business functions and, particularly, with the executive team.

They need to partner with the CFO - who should be the first to understand the SCM numbers. They need to closely align with the COO - who should be the first to grasp the complexity of the global supply chains and can act as an important ally.

Finally, they should team up with the CSO to build an alliance for revenue growth.

Forecast improvement, master data standardization, and warehouse optimization might not be as sexy as market entry strategies, acquisitions, or new product launches. But working together, SCM and senior management can identify the top-line potential and get the budget for important supply chain investments.

Related Article: A Portrait of the Supply Chain Manager

Article topics

Email Sign Up