DE roundtable on 3D printing now archived, available for on-demand viewing.

DE roundtable on 3D printing now archived, available for on-demand viewing.Last week, DE hosted a LIVE roundtable talk on industrial 3D printing, featuring Professor Timothy Simpson, Pennsylvania State University; David Sher, Analyst, SmarTech Markets Publishing; and Ryan Lozier, AM Engineer, Caterpillar Inc.

Sher, who recently published a report titled Opportunities for Additive Manufacturing (AM) in Aerospace in 2017, said, “The AM industry is worth about U.S. $7 billion. The potentials are huge, but it’s going to take time to develop.”

In Sher’s estimates, AM use in civil aviation contributes $582 million in 2016. It’s expected to reach $4.2 billion in 2027. (This number accounts for software, hardware, materials, and services.)

Long Journey from Concept to Flight

Among the people Sher interviewed for his report were engineers from Airbus. A 3D-printed hydraulic manifold—a highly flight-critical part—flew for the first time in March 2017. The project began in 2007. “It took them ten years to make it, test it, and verify that it could be flown,” said Sher.

In April 2017, Liebherr-Aerospace announced, “On March 30th, 2017, Airbus successfully flew Liebherr-Aerospace’s 3D printed spoiler actuator valve block on a flight test A380.” The company explained, “It offers the same performance as the conventional valve block made from a titanium forging, but it is 35% lighter in weight and consists of fewer parts.”

The opportunity to consolidate multi-part assemblies into single 3D-printed pieces makes AM ideal in lightweighting projects.

The opportunity to consolidate multi-part assemblies into single 3D-printed pieces makes AM ideal in lightweighting projects.Back to School to Design for AM

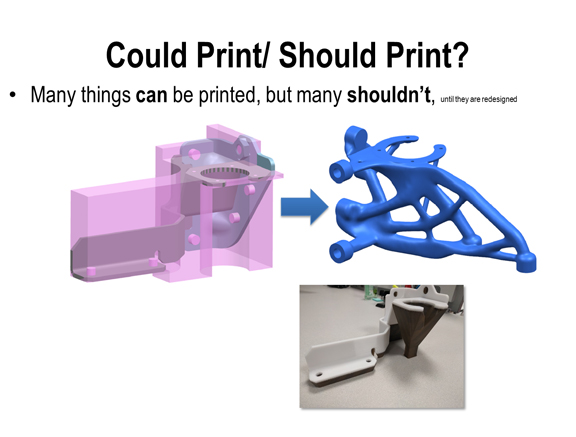

Lozier pointed out, “Many things can be printed, but that doesn’t mean they should be printed. There are many types of geometry not designed for AM. As a result, they often result in build failures.”

Part of Lozier’s job at Carterpillar is to teach CAD users how to design parts with print-suitable geometry. Reading off a whiteboard that lists things to avoid in AM, he advised, “No stamping. No sheet-metal fabrication. Things that you can make via other means, you should make them via other means. For instance, don’t print bar stocks, plate steels, and fasteners—you can buy them off the shelf. You shouldn’t 3D-print them, unless you’re trying to integrate them into a single part [as a way to consolidate parts].”

Panelist Lozier: Just because you can print something doesn’t mean you should print it.

Panelist Lozier: Just because you can print something doesn’t mean you should print it.So Many Ways to Fail

Professor Simpson shared a series of real-world failure examples, with causes ranging from inadequate support structure to small grooves that trap powder.

“If you take an existing part and try to 3D-print it, between the limited metal-powder choices and the small size of the build chamber, you could run into troubles. Also, think of support structures and overhang issues. In heating and cooling, your metal parts tend to curl up like potato chips. So if you’re putting down 20-, 40-, or 60-micron layers, you don’t have to have a whole lot of warping before the recoater blade smacks into it,” he said.

Despite these challenges, industrial deployment of AM remains attractive. It offers opportunities for lightweighting and part consolidation (redesigning a multi-part assembly into a single 3D-printed component) not achievable with traditional manufacturing methods.

In the instant poll conducted during the webinar, 41.9% of the attendees said they’re investigating or experimenting with AM technologies; 35.5% said they’re currently using it to make prototypes; and 19.4% said they’re using it to make end-use parts. It’s very likely a portion of the attendees use AM to produce both prototypes and end-use parts, but that number is unknown.

The webcast is now archived for on-demand viewing. You can access it here.

About the Author

Follow Robotics 24/7 on Linkedin

Article topics

Email Sign Up