Supply chain management (SCM) is an evolving discipline. The art and science of managing a global supply chain has gone through a transformation in response to changes in the way companies operate as well as a more complex and interdependent business environment. Practitioners need to keep abreast of these developments and adopt the appropriate mix of leadership skills.

More specifically, as the profession continues to grow beyond its physical distribution roots, supply chain managers require both broader expertise and deeper technical excellence. How to reconcile these two seemingly opposing demands is one of the most difficult leadership challenges facing SCM today.

By tracing the profession’s evolutionary track and changing profile, we can identify responses to these challenges and prepare practitioners for the leadership demands that lie ahead.

From Concept to Practice

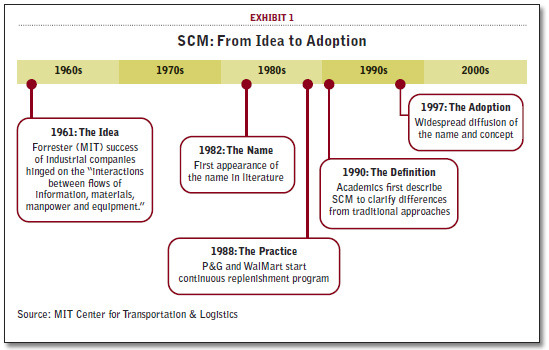

The SCM concept first arose from the work of Jay Forrester at MIT in the early 1960s. Forrester noted that success for a company relied on controlling and managing the “interactions between flows of information, materials, manpower, and capital equipment.” The first public use of the term Supply Chain Management did not occur until 1982 when Keith Oliver mentioned it in a Financial Times interview. (Exhibit 1, depicts the evolution of SCM from idea to adoption.)

Adoption of the SCM concepts was slow but incremental throughout the 1980s as traditionally silo-ed distribution, logistics, and transportation departments started collaborating. The Continuous Replenishment Program initiated by Walmart and P&G in the late 1980s is a prime example of the nascent initiatives and programs that were beginning to take place.

As is often the case, the academic community lagged the industry. Throughout the 1990s numerous universities created partnerships to formalize and flesh out this new integrated supply chain management concept. Consortia at MIT, Stanford, and elsewhere began clarifying the differences between older, more traditional logistics and the new supply chain practices.

In 1996, the consulting firms PRTM and AMR Research along with more than 50 manufacturers founded the Supply Chain Council. Over the next year, the organization developed and propagated the first set of comprehensive, cross-company metrics and approaches that track the information and material flows described by Jay Forrester 30 years earlier. The SCOR framework of Plan, Source, Make, and Deliver shifted the way companies considered and measured their extended operations.

SCM disciplines continued to become widely adopted throughout the 2000s. Today, SCM is considered common practice in North America and Europe, and, increasingly, in the rest of the world.

Supply Chain Evolution and Organizational Structures

The acceptance of SCM as a discrete discipline has helped to revolutionize the way companies are organized and run. SCM has redefined the traditional view of the company as a set of independent functions that operate within established boundaries and rules.

This functional view of the world divided the product and information flows into independent responsibilities such as purchasing, inventory control, warehousing, materials handling, order processing, transportation (inbound separate from outbound) and customer service. Each of these functions received inputs from an upstream silo, performed some action, and sent their results to a downstream function.

This waterfall process between silo-ed functions was the norm. And it was relatively easy to manage; each function had very clear boundaries and metrics. Managers made decisions within their own four walls, and the complexity of these choices was defined by the limits of the available resources.

From a decision-making perspective this silo-ed structure allowed each manager to focus on a simple objective function with few variables to consider and limited by many constraints. The constraints captured the various inputs coming from upstream departments and requirements arising from downstream functions.

As firms loosened these functional boundaries, departmental walls became more porous, making it possible, for example, for transportation to work with customer service to evaluate the impact of specific delivery windows. This new regime was enabled by logistics functional areas that looked at a wider range of trade-offs between the once silo-ed functions within the organization.

Managers developed cross-company communications channels. They were now able to provide feedback on the implications of their decisions to colleagues in upstream and downstream departments. Other managers could now build this information into their decision making. Supply chain partners were part of this cross-functional dialogue, albeit to a limited degree.

In this freer environment the flaws in the silo-ed approach became apparent. Decisions made in one function were analyzed in terms of their impact on other functional areas; enterprises were becoming more complex and intertwined. What was once a constraint in the decision making process, now became a new variable.

When decisions have more degrees of freedom, they become more complicated and involve trickier trade-offs. Managers needed to engage with functions beyond their sphere of control. In some firms this was resolved by creating matrix organizations with dual-reporting structures designed to balance conflicting internal objectives.

These changes began to encompass the multiple partners and enterprises along the flow of product and information from initial manufacture to final consumption. The decisions made within the product design process (pertaining to materials, sources, packaging, and so forth) became critical issues for the transportation and fulfillment functions, for example. More and more people, organizations, and perspectives, were included in the decision-making process.

As SCM expanded to include both suppliers and customers along the chain, these decisions became even more convoluted. The different decision makers were no longer under one roof or in the same company. In many cases, suppliers were also supplying competitors, and trading partners’ goals were misaligned. Downstream customers (such as retailers) had differing strategies, objectives, and missions. The business functions needed to properly align with and reconcile this increase in complexity.

As managers engaged with extended supply chain partners, it became more difficult to exert direct control over operations. Internal organizational restructuring was less effective and required more “soft” skills than before. There was greater recognition of the need for persuasion, collaboration, and joint-design practices across the extended supply chain.

In its current form, SCM has flipped 90 degrees from a vertical, within-the-firm orientation, to a more horizontal flow that mirrors the flow of products, information, and money. Partners do not necessarily share the same culture, objectives, language, geography, or level of sophistication.

Global Shifts Reshaping SCM

These changes have not taken place in a vacuum. External developments have also reshaped SCM over recent decades.

Globalization has led to the dispersion of supplier networks across the world, for example, making collaboration with trading partners much more complex.

The world order is now very different compared to 30 years ago. In 1982 China was the 24th largest trading partner with the United States—just behind Switzerland. Within a few decades it became the second-largest, just behind Canada. Trade flows have shifted both nationally and internationally in line with this economic reconfiguration, requiring companies to adapt their supply chains to the ever-changing commercial map.

At the same time, shorter product lifecycles for most consumer products have led to a proliferation of SKUs and generated even greater complexity in supply chains.

Other challenges that have emerged over this period include:

- Measuring the performance of a supply chain that crosses multiple entities that do not fall under the same control. End-to-end metrics are attractive and comprehensive, but it can be difficult to assign responsibility for measuring performance in today’s globe-spanning supply chains.

- Making trade-offs between the various players in a supply chain. For example, how are the benefits shared among trading partners in the extended supply chain.

- Ensuring that each partner in a supply chain has visibility into inter-organizational product flows.

- Coordinating operations in markets or mega-cities with very different levels of economic development and varying levels of physical infrastructure.

The SCM Response

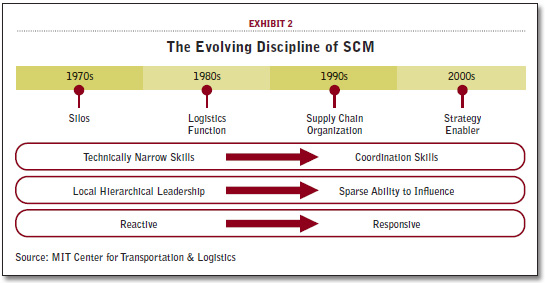

SCM has responded in many ways to these changes and related challenges. The emphasis on silo-based operations that focus on product delivery and quality in the 1970s, and the cross-functional coordination that is characteristic of the 1990s, have given way to yet another role for SCM: that of strategy enabler. (Exhibit 2) Nowadays the profession is being asked to anticipate competitive challenges, obstacles, and opportunities.

In effect, SCM has become both a shock absorber and a bridge. It buffers the firm against the impact of volatile demand, uncertain supply, and disruptions. And it serves as a bridge between the organization and its trading partners, including both suppliers and customers. With these dual roles (shock absorber and bridge) the profession has, by default, become responsible for ensuring that the company—and specifically its end-to-end supply chain—is resilient.

However, the move away from functionality towards strategy enablement requires SCM to adopt the skills, technology, metrics, and risk management disciplines needed to fulfill the new role.

To get a sense of this shift, consider the range and types of skills SCM leaders needed in the functional supply chain, compared to those required in the more strategic regime in which they now find themselves.

Horizontal communication. Traditionally, supply chain leaders were functional experts who were technically narrow and had little incentive to get to know other functions. In today’s supply chain, the critical skill is coordination. Each decision impacts—and is impacted by—other aspects of the supply chain. Maintaining open and clear communications is very important, and this requires managers to have multi-lingual capabilities and multi-cultural awareness.

Technical competence. The dominant technology used to be localized and isolated optimization tools. Optimization-based decision support systems for individual functions rose to prominence during the late 1980s to the 1990s. Transportation and warehouse management, production planning, and other systems emerged during this time. These solutions tended to be narrowly focused within a function.

Today, high-powered optimization engines are still used, but the more critical components focus on visibility and coordination aspects. Technologies that connect multiple organizations such as CPFR and collaborative exchanges support the flow of data across supply chains.

Collapse of the hierarchy. Previously, supply chains managers had local and controllable influence over all aspects of their function. This typically led to a hierarchical reporting structure where a direct style of management was most common. Most of the functional managers developed “hard” skills for leading people and organizations they controlled directly.

Today, the supply chain manager’s reach exceeds his or her grasp. Leaders are required to influence behavior across the entire supply chain to include organizations and people who do not report to them or are not even in the same organization. These leaders have become influencers rather that dictatorial, hierarchical managers; they are required to exert influence indirectly and achieve change through persuasion.

More yardsticks. In the functional world, performance measurement systems were defined by a bounded set of activities with a single focus. Today, these systems need to be multi-tiered and multi-faceted to capture the breadth and depth of company operations.

Risk factors. Risk management tended to be reactionary in the functional era. The strategy was typically to build robustness (through excess inventory or capacity) into the individual functions or areas, so they could weather disruptions to supply, demand, or production. Today, risk management has transformed into one of supply chain management’s primary roles. The new emphasis is on developing planned responses for potential disruptions, and strategies for creating opportunities for flexibility within the supply chain.

Pushing the Skills Envelope

The net effect of these changes is that SCM has become a broader and deeper discipline. The breadth of the supply chain is now global, and managers are expected to work with a wider variety of people, cultures, and geographies. The increase in depth is a reflection of the more complex relationships between the functions and the sophistication of the different technologies and tools in use today.

In this environment supply chain managers are being pulled in two directions. They need to become generalists with good communication and coordination skills, and also specialists who can lead within their domain and, in some cases, offer deep technical expertise. In other words, these leaders have to be exceptionally well-rounded professionals both as team members and individual executives.

In a recent interview with MIT CTL, Christine Krathwohl, Executive Director, Global Logistics and Containers, General Motors, emphasized the importance of a broad background to her role as a logistics leader.

Krathwohl expressed it this way: “I tell every young person who wants a career in supply chain or logistics that I reached my current position largely due to the varied experience I gained throughout my career. My time in manufacturing has allowed me to understand the requirements and challenges of our internal customers, and has given me a level of credibility and respect within the organization.

Also, my experience working on the supply side allows me to understand the challenges that suppliers face, and that helps me to build a higher level of trust with these companies.”

There are six areas of expertise that are particularly important for current and future SCM leaders.

- More emphasis on a blend of “soft” and “hard” or analytical skills.

- The ability to manage and cultivate deep analytical expertise within the organization.

- Being able to excel as leaders of virtual, multinational teams.

- To appreciate big-picture issues and communicate vertically and horizontally.

- Skilled at integrating complex technology systems that span multiple functions and multiple organizations.

- The ability to engage in strategic thinking at both company and industry levels.

The accompanying sidebar relates what some leading supply chain practitioners consider to be the key skills needed to advance a career in SCM.

Developing the Leadership Pipeline

Knowing which skills are needed to perform as a supply chain leader is one challenge; another is figuring out how to develop and retain the individuals who fit this profile.

Books have been written about identifying and nurturing corporate leaders, and we do not have the space here to do justice to this subject. But here are some strategies that are important in the SCM domain.

Give them a career path to the top. This may seem obvious, but in many companies SCM is still regarded as a low-profile, tactical role that does not extend beyond the operational trenches. Truncating a professional’s career prospects in this way is a sure way to stymie their ambitions and, if they are capable, to lose them.

A number of enlightened companies realized this some time ago and have taken action. Electronics manufacturer Intel, for example, has established a well-defined ladder for SCM that parallels the paths taken by the company’s engineering staff. Mapping such a path to the top requires leaders from HR and SCM to work together to establish career milestones and incentives.

Establish job rotation programs. A well-planned system for giving individuals temporary assignments in other departments and/or geographies, gives prospective leaders the breadth of experience they need to fulfill their ambitions. Moreover, providing new challenges and fresh experiences helps to keep these individuals interested in the organization.

Within her industry, GM’s Krathwohl noted, “If you can get a job rotation on a plant floor, my advice is to take it. It’s the best experience you will have in terms of people dynamics and the operational environment.” Encouraging individuals to venture outside their comfort zones is also important. “Even within the job or function, you have to look outside of the box; what special assignments can you take, and what cross-functional teams can you be on to gain more experience?” she advised.

Overseas assignments add both depth and breadth to a supply chain manager’s skills set. “We transfer and rotate people in terms of countries,” said the HR vice president of a global apparel manufacturer. These placements are carefully managed. For example, individuals are matched to the maturity of the overseas business. When the company was acquiring a business in Asia, “the type of people I need to do the start up in transition are not the type of people I need going forward,” the HR executive explained.

Build bridges with HR. It is difficult to develop effective leadership programs when HR managers’ knowledge of the supply chain function is incomplete or shallow. Some organizations have a HR manager dedicated to SCM; others actively encourage collaboration between respective functions. As a senior HR executive responsible for SCM talent said: “If I don’t understand where in the world we are growing and where we need resources, I can’t develop effective programs like assignment rotations.”

Encourage people to graduate through the ranks. A major retailer has made it mandatory for staff to have worked in certain mid-level positions before they can be considered for senior roles. Prospective leaders must have experience in managing a distribution center, for example. The aim is to make sure that these individuals are well-rounded both in terms of their own skills set and their view of the company.

Discourage the strategic bias. This is related to the above point, but pertains to the tendency to become obsessive about working only at a strategic level. For example, some companies complain that graduate hires expect to be groomed immediately for strategic positions even though they have not learned the ropes in more tactical managerial posts.

A senior supply chain executive in a global apparel firm lamented that in his experience, too many talented individuals refuse to even consider a role unless the word “strategic” features somewhere in the job title. An ambition to become a strategic wizard is fine as long as the individual concerned is prepared to gain experience in other areas first.

Invest in ongoing education. It almost goes without saying that given the pace of change and the intensity of today’s competitive environment, companies need to invest in ongoing training and education to keep leaders’ skills up to date.

Be Prepared

It is impossible to know for certain which specific trends will shape supply chain leaders a decade from now. However, the chances are that new dimensions—both in terms of the profession’s depth and breadth of influence—will be added to the role. Here are some examples that are already appearing on the radar screen.

- Much more emphasis on environmental and social awareness.

- The need for politically savvy individuals who can navigate a constantly changing world.

- An intimate knowledge of social media and related communications technologies and channels.

- The ability to interact with non-commercial organizations such as governments and NGOs.

Adding to the complexity is that SCM is evolving at different rates around the world. Emerging economies are still in catch-up mode compared to many western countries, but the gap is closing fast. And the SCM leadership challenges in these countries are unique in a number of ways.

As is the case in the SCM space generally, rather than trying to predict which skills sets will be a top priority 10 years from now, a more effective approach is to be prepared to meet these demands by being flexible and agile today.

Skills that Advance Supply Chain Management Careers

Article topics

Email Sign Up