In The Perfect Storm, Sebastian Junger chronicled the story of the six crew members on board the Andrea Gail, a swordfish boat out of Gloucester, as they battled a once-in-a-century meteorological cataclysm off the coast of Newfoundland in October 1991.

The devastating storm was created by the confluence of three extreme meteorological forces: an icy cold high pressure system, a low pressure system, and the remnants of tropical Hurricane Grace. It was a colossal winter-summer collision of an Arctic storm and a tropical hurricane. When the low pressure system met the high pressure system, they formed a non-tropical Atlantic storm that later absorbed Hurricane Grace.

Such events are rare, but when they happen, they bring forth enormous amounts of destructive energy. During The Perfect Storm, gale force winds “blasted over the ocean at more than 100 mph. Ocean waves peaked at 100 feet, the height of 10-story buildings,” wrote Beth Nissen, a reporter for CNN.com. As anyone who has read the book or seen the movie knows, the ship and crew succumbed to the power of the wind and waves.

Based on our research, which was supported by the Center for Supply Chain Research (CSCR) at the Smeal College of Business, at The Pennsylvania State University, we believe a supply chain talent perfect storm could be in the offing.

Our conclusions were drawn from a review of the literature, reports from key organizations, and a Supply Chain Leaders Forum (SCLF) sponsored in October 2012 by CSCR. The Leaders Forum brought together more than 70 top supply chain and human resource professionals from a variety of companies and industries to address the challenges stemming from supply chain talent.

Based on our review, we have observed a number of key emerging trends that individually create tension and potential disruptions in the supply chain talent pool. Either of those on their own can create challenges for a supply chain organization similar to a hurricane or a severe winter gale. At the same time, like The Perfect Storm, there is the prospect of these trends colliding to create a supply chain talent “perfect storm.”

The goal of this article is not to take a strong stance on if or when the storm will occur; like the weather, that is hard to predict. Rather, consider this paper a “storm warning.” Just as serious seafarers knowledge of atmospheric conditions is a large part of seamanship, proactive organizations need to recognize the importance of understanding the vagaries of the business atmosphere in devising business strategies.

In the following, we describe key emerging trends in supply chain talent that individually create tension in the supply chain talent pools, along with strategic recommendations to weather and survive any coming storms.

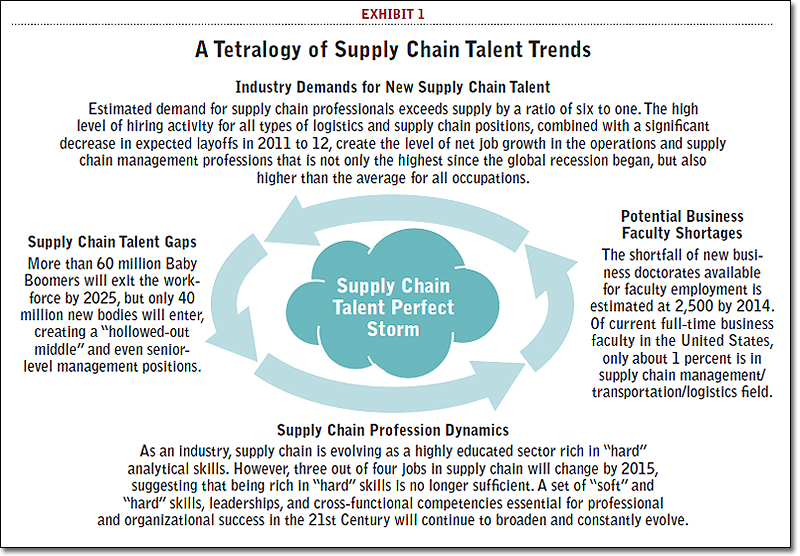

A Tetralogy of Supply Chain Trends

At least four trends—a tetralogy—are forces of increasing magnitude that create strains in the supply chain talent pool (Exhibit 1). They include:

1. Industry Demand for New Supply Chain Talent

2. Supply Chain Talent Gaps

3. Supply Chain Profession Dynamics

4. Potential Business Faculty Shortages

Each of these four has an impact on the others.

1. Industry Demand for New Supply Chain Talent

The demand for supply chain talent has been on the rise across industries and types of logistics and supply chain positions. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, jobs in logistics are estimated to grow by 26 percent between 2010 and 2020, an average growth rate that is nearly twice as fast as 14 percent of all occupations.

The supply chain job growth has been affirmed by a variety of industry associations. For instance, CSCMP’s Career Center reported “very strong” hiring activity and job postings for all types of logistics and supply chain positions in 2011 and 2012. Similarly, surveys conducted by the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) indicated steady and strong climbs in hiring in both manufacturing and nonmanufacturing sectors in 2011. Already, demand for supply chain professionals is estimated to exceed supply by a ratio of six to one, according to R.J. Bowman, author of The Secret Society of Supply Chain Management.

2. Supply Chain Talent Gaps

The gap between the demand and availability of supply chain professionals is only going to get wider. Consider that there are an estimated 76 million Baby Boomers in the United States who are turning 65 at the rate of one every eight seconds, according to a report by Steve Minter in Industry Week.

At this rate, the US Census Bureau projects that more than 60 million Baby Boomers will exit the workforce by 2025. Given that there are fewer GenXers than Baby Boomers, only 40 million new bodies will enter the workforce. As a result of this demographic trend, talent shortages that already surfaced at most occupational levels in supply chain are most acute in mid-management positions (a “hollowed-out middle”) and even senior-level management positions.

3. Supply Chain Profession Dynamics

It’s not just that there is a smaller pool of potential professionals available for the future, there is also a growing skills gap that is exacerbated by the transition from industrial economy to information/service economy.

By all accounts, today’s business environment demonstrates less standardization, higher complexity, longer learning cycles, higher dynamics, and higher degree of talent intensity. For evidence, consider that jobs requiring highly skilled professionals continued to grow even during the recent recession. Accordingly, supply chain as an industry is evolving as a highly educated sector rich in professionals with “hard” analytical skills.

However, the ongoing transition to a knowledge-based, globalized economy carries with it changing supply chain profession dynamics. In fact, it is projected that three out of four jobs in supply chain will change by 2015, and that 60 percent of all new jobs in the 21st century will require skills that only 20 percent of the workforce possesses. For supply chain as an industry, this means that being an industry rich in “hard” analytical skills is no longer sufficient.

On the contrary, a set of skills, leadership, and cross-functional competencies essential for supply chain professional and organizational success in the 21st century will continue to broaden and constantly evolve. Already, there is a shortage of highly skilled workers who possess those broader business skills.

4. Potential Business Faculty Shortages

What about the capacity of academia to create new talent? The outlook does not look sunny on that front either. According to the International Business School Data Trends, published by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), the number of full-time business faculty in supply chain management, transportation, and logistics has been consistently below 1.5 percent of all-field business faculty both in the United States and worldwide.

With an average of just 365 U.S. supply chain business faculty members between 2009 and 2013, this relatively diminutive body could shrink even further given the pending retirements of baby boomer-aged faculty. Adding to the predicament is the somber outlook for the number of new doctorate graduates available for faculty employment in U.S. universities, despite the fact that more than half of business doctorates graduated each year earned their degrees from U.S. schools. According to the Doctoral Faculty Commission, the shortfall of new business doctorates by 2014 is estimated at 2,500.

A number of factors are contributing to these shortfalls. For one, at least 15 percent of new doctorates choose to take government or industry positions rather than academic positions, while many others are hired to teach outside of the United States. For another, the number of new students accepted into business PhD programs in U.S. universities has been weakened by tough budget pressures. Finally, the PhD completion rate is lugubrious: Almost half of all new business doctoral students do not complete their degree programs, resulting in the perceivably slim number of business-doctorates-to-be.

The ramification of the latter two factors can be gauged from the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s 2011 Survey of Earned Doctorates from US Universities. According to the survey, the number of doctorate recipients in business and management averages 2.8 percent of doctorate recipients in all fields of study during 2001–11 vs. approximately 16 percent in science and engineering fields.

The Supply Chain Talent Perfect Storm

The deleterious effects of each of these forces on the availability of supply chain talent are already individually at play. What happens if they collide and converge? They could create a supply chain talent “perfect storm” that could have severe repercussions:

- Breadth - The effects could permeate across all supply chain functions.

- Depth - The effects will be felt from top to bottom.

- Longevity - The effects won’t simply blow over quickly.

In essence, organizations in the midst of the storm will find it increasingly difficult to simultaneously search for the right talents to back-fill those who retired or about to retire, raise the skill sets of existing talents to meet the needs of a changing environment, and groom high-potential talents into future supply chain leaders.

What’s at stake here?

While the talent shortage could affect value creation, performance, and competitive advantage in many ways, the underlying theme in all of them boil down to a single strategic asset: supply chain knowledge (SCK). That’s the knowledge of the products, processes, and partners within the supply chain.

How important is SCK? Paramount! For example, a recent meta-analytic study examined the data from 35 published academic papers on supply chain knowledge and performance. The authors concluded that SCK was a significant indicator of the performance of supply chain organizations.

“While firms most likely want to devote time and money to cultivating a variety of strategic resources,” the authors wrote, “their investments in building SCK may offer particularly handsome returns.”(1) Unfortunately, the ability of organizations to invest in SCK in the future may be significantly hampered by the perfect storm.

Five Strategies to Weather the Storm

While specific activities of talent management differ by organization, talent management programs at organizations participating in the Supply Chain Leaders Forum have certain characteristics in common. The most important is that they have developed future-focused, integrated talent management programs that are aligned with corporate strategies. Underlying these programs are five strategies contrived to ensure that the organizations are prepared to stay afloat in the midst of the perfect storm.

Strategy 1: Prepare the vessels by constituting employee value propositions

Sailors prepare for heavy weather by ensuring that the vessel is structurally sound, well provisioned, and outfitted with proper operating, maintenance, safety, and emergency gear and systems.

To prepare for the supply chain talent perfect storm, organizations’ talent management programs need to have structurally sound employee value propositions that span opportunity, work, rewards, people, and organization. Specifically, employees should be provided with a career roadmap and opportunities to acquire the skills they need to climb the leadership ladder and broaden their career potential.

These roadmap and opportunities, as well as compensation and incentive programs, should be designed to reflect individual skill assessment (to identify skill gaps), learning pace and style, and personal objectives such as progress in life and career. All activities must be accompanied by specific goals and timelines against which each individual is evaluated and development plan updated.

Strategy 2: Plot safe passage by mapping talent needs

When a storm is gathering at sea, the first and foremost strategy is to work out the vessel’s current position and plot the safest course to sail through the stormy water. This action also means that one continues to keep an eye open for changing conditions that render the current forecast obsolete and revises the course as needed.

In a similar vein, mapping talent needs entails identifying the “must have” competencies required by an organization. That is followed by an assessment that identifies the disparity between existing skill sets, must-have abilities and the skill sets that are integral to meeting business strategies. Such a competency framework needs to be future-focused and future-proofed by continuously reevaluating and updating the pivotal skills that will be required in the future to compete in an ever-changing business environment.

The goal is to ensure that talent is recruited, developed, evaluated, and compensated in line with the performance needs of the business. To achieve this goal, a flexible architecture of talent management programs is important for organizations’ ability to adapt and revamp their approaches accordingly.

Strategy 3: Batten down the hatches by focusing on retention

In inclement weather, seafarers once used strips of wood called battens to secure covers over the hatches, preventing the loss and damage of the precious cargo on board.

In general, supply chain executives expect their most talented employees to leave at some point. However, a tremendous amount of voluntary turnover is occurring today, despite an uncertain economy. The upward trend of voluntary turnover rates is likely to become even more pronounced in the future because of the free agent mentality—the willingness to leave current employer for more money and/or for a bigger career opportunity—particularly among young professionals.

In fact, voluntary turnover rates are increasing significantly in Generations X and Y that currently accounts for more than half of the U.S. workforce, compared to older Baby Boomer and veteran counterparts. Supply chain organizations that want to weather the storm need to batten down the hatches and protect their most valuable employees during inclement weather.

Strategy 4: Reef your sails by investing in talent and leadership development

To guard against the adverse effects of strong wind during heavy weather, seafarers reef their sails to reduce the area of a sail exposed to the wind. The rule of thumb is to reef before it is needed as it is always easier to reef the sails before rather than during a storm.

To reduce exposure to the supply chain talent perfect storm, professional development plans are increasingly used to convert a critical mass of “labor” into “talent and leadership.”

This strategy is reflected in the fact that a particularly popular track for new entrants into the supply chain management and logistics field is professionals who earned non-logistics/SC-related undergraduate degrees and learned through their employers’ development programs.

Not surprisingly, there has been a steady increase in investment in high-potential and leadership development, and increase career path opportunities. Certain traits distinguish heavy-weather talent development programs from traditional counterparts.

First, heavy-weather development programs balance a mix of formal programs, such as university courses and expertise development and certification, and informal programs, such as on-boarding processes, on-the-job training and mentoring programs.

Second, the heavy-weather development programs shift from training to learning, and from traditional tower-focused to T-shaped talent development approach. The learning-based, T-shaped approach hones in on core supply-chain technical skills, while simultaneously embracing leadership and globally integrated, cross-functional capabilities.

Commonly implemented programs are global mobility programs and job rotations or cross-functional assignments. The former, global mobility programs, help develop the next leadership generation by creating opportunities for individuals to become more culturally aware and apt in a globalized business world.

The latter, job rotations, aim to broaden the perspectives of functional specialists in terms of the roles and responsibilities as well as the opportunities and challenges inherent in managing diverse value-added activities throughout the organization.

Unlike those in traditional programs, job rotations in heavy-weather development programs are not limited to related disciplines, such as procurement, manufacturing, and logistics, but also include nontraditional areas like human resources and marketing, to develop talents with domain knowledge and establish relationships in broader areas of the organization.

As an example, Ingersoll Rand uses the “2 x 2 x 2” rule that a senior manager must meet; that is, she/he must work in at least 2 different business units, in two different functional areas, and in two different countries, according to Industry Week’s Steve Minter.

Strategy 5: Stem the tide by landing top talent early for the next decade

Nautically speaking, a ship stems the tide when she intentionally sails against the tide at such a rate that she is able to overcome its power, thus preventing the mounting force of the tide from stalling or capsizing the ship.

Stemming the tide in this context calls for the creation of a talent pipeline, notably for positions that are typically difficult to acquire, by collaborating with colleges, universities, and even high schools.

This strategy allows the organizations to introduce high school juniors and undergraduate seniors to supply chain careers, hence raising the level of awareness of the profession in order to encourage more young people to enter the field. In addition, the organizations are more actively engaged in various educational activities, such as the following:

- Participating in developing industry-driven curriculum.

- Offering scholarships to students based on scholastic achievement and interest in pursuing careers in the supply chain management field.

- Offering paid internships or sponsoring projects, consulting assignments, and/or research that provide real-world experiences and help foster development of future supply chain executives.

- Being “guest lecturers” to better disseminate insights from industry into supply chain programs to support the development of theory into practice.

In effect, this industry-academic collaborative relationship is mutually advantageous to both parties. The industry is able to land work-ready supply chain talents early for the next decade; while the academic institutions are able to stay informed about the changing educational needs of industry to auspiciously further growth and development of supply chain education programs. Conceptually, these efforts could be thought of as “customer managed inventory.”

Will the supply chain storms collide? And if so, when? We’re not sure. However, the steps supply chain organizations take now could mean the difference between riding out the storm or sinking under the waves.

Footnotes:

1 Wowak, K. D., Craighead, C. W., Ketchen, Jr., D. J. & Hult, G. T. M. (2013): Supply Chain Knowledge and Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Decision Sciences 44 (5), pp 843-875.

About the Authors

Kusumal Ruamsook is a Research Associate at the Center for Supply Chain Research, Smeal College of Business, at The Pennsylvania State University. She can be reached at [email protected]

Christopher Craighead is the Director of Research at the Center for Supply Chain Research and the Rothkopf Professor and Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management at the Smeal College of Business. He can be reached at [email protected].

For more information, visit the Center for Supply Chain Research

Related: Penn State Smeal and CorpU Launch Supply Chain Leadership Academy

Article topics

Email Sign Up