No doubt many readers of this article already tap their mobile phones to get an Uber to the airport.

Similarly, they've used the Airbnb app to find a nice place to stay for that long weekend.

So it shouldn’t be a big surprise for them to learn that warehouse services can now be acquired in similar ways.

Dynamic on-demand warehousing is emerging as a viable way of purchasing warehousing services on demand - paying only for what is used instead of owning distribution centers or signing contracts with third-party logistics providers (3PLs).

As with Uber, Airbnb and a host of other shared-economy services, the actual pay-per-use transactions occur in an electronic marketplace.

The approach can extend to a company’s entire warehousing strategy, or it may supplement an existing logistics network built on long-term contracts. In either case, it allows the company to adapt quickly to variable demand and cost conditions.

Dynamic on-demand warehousing can be particularly useful for e-commerce, where retailers typically face high demand uncertainty and often have significant capital constraints.

Additionally, dynamic on-demand warehousing allows e-commerce retailers to rent small units of capacity in many parts of the country, enabling quick delivery to wider pools of customers.

This article introduces the idea and demonstrates its value with a brief case study.

Warehousing Tries to Keep Up with eCommerce

Before the advent of e-commerce, many retailers used warehouses as intermediate storage points (distribution centers or DCs) to supply their stores; it is still a common way to manage distribution.

A retailer could use a network consisting of a few Distribution Centers (DCs), each serving a “region” comprising many states, with replenishment lead times of a few days.

According to the latest Annual State of Logistics Report from the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), total logistics activity in the U.S. in 2014 cost $1.45 trillion - roughly equal to 8.3% of gross domestic product. Of this, $900 billion was in transportation costs.

Although warehousing alone accounts for only 10% of total logistics cost at $143 billion, its activities have a significant effect on transportation costs: A more extensive network reduces outbound shipping costs (which are generally more expensive per unit), despite some increase in inbound transportation costs.

With the development of e-commerce, however, the traditional warehousing model began to fall short.

E-commerce creates significant challenges in terms of customer expectations, compared to traditional retail. In general, outbound shipping with e-commerce features very small quantities sent directly to individual customers.

Shipping time is absolutely critical: Many customers now expect their items to arrive inside two days, and more and more retailers are offering same-day delivery. As an example, Walmart is reportedly targeting free two-day shipping using a network of eight DCs, supplemented by its retail stores, according to Fortune.

Furthermore, e-commerce demand can be highly variable, influenced by social media and faster news cycles in the Internet media.

Moreover, the sheer acceleration of e-commerce presents logistics challenges: Total U.S. e-commerce sales in 2015 came to $340 billion, comprising 7.5% of total retail, and growing at nearly 15% year over year, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Such factors are forcing significant changes on the warehousing industry. The changes are not simply because e-retailers keep more inventory in warehouses because, by definition, they have no brick-and-mortar stores.

Overall, demand for warehousing space is growing, as is the need for an efficient warehousing and distribution strategy. CSCMP’s State of Logistics Report notes that the national vacancy rate had dropped by 2.7% to 7% from 2013 to 2014.

In some areas, shortages are rapidly driving up warehousing costs; according to the Wall Street Journal, e-commerce has hiked rates by almost 10% in a year, with the San Francisco bay area seeing a jump of more than 28% in that period.

A Need for Alternative Warehousing Solutions

For e-retailers, shipment options have been challenging indeed. Traditionally, their options have been these:

- Startup–drop ship. If the retailer owns its own manufacturing/assembly facility, initially it may ship directly from that facility. Many small e-commerce retailers start this way.

- Self-owned network. If the retailer operates its own warehouses, it is unlikely to have the scale and financial resources to build an extensive network. As a result, the average distance to the customer is high, resulting in high shipping costs and longer delivery times.

- Network outsourced to 3PL. Although this offers a little more flexibility compared to a self-owned network, many 3PLs demand commitments of one year to three years. This effectively locks the retailer into a fixed structure for several years.

- Distribution outsourced completely. Amazon.com, for instance, offers a service called “Fulfillment by Amazon” (FBA) wherein it distributes other retailers’ products through its network. Although this can provide speedy service to customers, the costs can be high and many retailers are wary of handing over a core part of the business to a top competitor.

A Role for Dynamic On-Demand Warehousing

Dynamic on-demand warehousing, quickly matching those needing space with facilities that have space available, is emerging to help facilitate the pace and scope of e-commerce’s logistics needs. Several new companies have launched recently to provide the on-demand service.

It is “dynamic” in the sense that the retailer can change the configuration frequently: based on demand conditions, warehouse space could be deployed at different locations, for different volumes, in a dynamic fashion. Its order management system and warehouse management system can link the retailer’s systems with those of the warehouse provider.

The idea is that the shipper has access to a large network of warehouses, and can activate services “on the fly,” ranging from bulk pallet handling to fulfillment, in small to large volumes and for relatively short times.

For example, a small e-commerce retailer may decide to create half a dozen different distribution points, with as few as 50 pallets at each warehouse and little to no fixed time commitment. The warehouse provider would use its own labor and equipment to perform standard and optional services such as receiving, shipping, case pick, item pick and packing, and would charge the retailer on a per-unit basis.

In such a system, the retailer incurs no upfront fixed costs, and gains significant flexibility. Of course, the unit cost charged by the warehouse provider may be higher or lower than what would be incurred by the retailer if it operated its own high-volume, high-utilization warehouse. But this is the benefit of dynamic on-demand warehousing: The retailer gains flexibility and avoids capital expense, even if sometimes the per-unit cost is higher.

Dynamic on-demand warehousing is best suited to retailers with small but highly variable demand, such as emerging e-commerce retailers. For mid-size retailers, it can act as a buffer to handle unexpected demand variability, complementing a primarily self-operated and 3PL-based network. (It is of little advantage to the e-commerce activities of large retailers, such as Walmart and Target, which handle large volumes and see fairly predictable demand.)

The new flexible warehousing concept is a good example of what has been called “platform capitalism” - one of the fastest growing and most significant trends in the business-to-business (B2B) world, based on reports in publications such as The Guardian and the Institute for Network Cultures.

Over the last decade, electronic marketplaces have proliferated, providing an ever-wider range of services and business activities. The earliest marketplaces were largely business-to-consumer (B2C), dealing in tangible products - Amazon.com started out with books, and Zappos with footwear.

Increasingly, e-exchanges handle a host of services for businesses, ranging from basic administrative tasks to the outsourcing of large-scale manufacturing activities. For example, Kickstarter provides a platform for online fundraising; Innocentive crowdsources new ideas for participating companies.

In much the same way, new platform providers such as FLEXE “match-make” those in need of warehousing space with places that can provide it.

Compared to the warehousing services offered by traditional 3PLs, dynamic on-demand warehousing makes it possible to rent significantly smaller spaces for short time periods.

This is analogous to what already happens in the trucking sector, for instance, where a retailer can operate its own fleet of vehicles, set up long-term contracts with large trucking companies or use a Web-based freight exchange to contract for individual loads with one truck at a time. Moving from running a fleet of trucks to using a freight exchange, capital expense decrease, unit costs rise and flexibility increases. Those tradeoffs are exactly the same with warehousing.

Value for Warehouse Operators

Dynamic on-demand warehousing is of real value for warehouse owners as well. Building a warehouse can be expensive; any unused space has an opportunity cost.

Even if a warehouse owner/operator has long-term contracts with retailers or 3PLs for much of its space, any remaining space can be turned into a revenue-generating asset by “registering” it on a dynamic on-demand warehousing marketplace.

Depending on its operating costs, opportunity costs and market dynamics, a warehouse owner can choose a price that may be more, or less, than the rates it charges its existing clients.

Case Study: A growing e-commerce retailer that faces variable demand

To illustrate the economics of dynamic on-demand warehousing and compare it to a traditional operation, let’s consider a simple case study of an e-retailer with a single plant in Ontario, California (the retailer imports all of its goods through the port of Los Angeles).

We’ll assume that the retailer has a SKU count of 500, a total annual order quantity of 1 million units, an average of 1.5 units per order; and customer demand mirrors that of the overall U.S. population. The Ontario facility spans 95,000 square feet and has a 95% utilization level. Let’s look at three test cases to see how dynamic on-demand warehousing stacks up.

Test Case 1: One warehouse serving all customers in the U.S.

Early on, the retailer simply uses small package delivery to ship to its customers spread across the U.S. Using demand information, standard industry transportation costs and a fixed warehouse location near the Ontario plant, we can calculate the cost of operating the network. (For this, and all of the network design in our study, we use Tactician, a Web-based network optimization software.)

Total cost per order comes to $11.89, with transportation costs per order of $9.53 and $2.36 in warehousing costs per order. One-time fixed cost is $225,000 (for operation start-up, equipment installation, etc.); the three-year locked-in lease for the warehouse costs $2 million. Total annual cost for the one-warehouse mode: $11.9 million.

Of that total cost, about 80% is outbound transportation, from the warehouse to the end customer. Inbound transportation rates are very low, but the distance is minimal. So, in order to reduce transportation costs and in turn to lower total costs and improve service levels, it would make sense to have multiple warehouses across the country.

However, this also implies higher warehousing costs as the fixed costs would increase when more warehouses are added to the network.

Also note that the existing network delivers only 12% of orders within two days. As the e-commerce industry moves toward faster and faster delivery times, it is important for the e-commerce company that its customer service level is as high as possible while maintaining reasonable costs.

Test Case 2: 70% and 90% orders fulfilled within two days

Let’s now imagine that the e-retailer’s goal is to deliver 70% of the orders within two days, at minimal cost. Our calculations, using the same demand and shipping information as described above, as well as industry standard warehouse costs, show that the retailer’s optimal network has three warehouses, in California (22,000 square feet), Illinois (38,000 square feet) and North Carolina (34,000 square feet). Utilization of each is 95%.

Now the total cost per order averages $10.25, with transportation cost per order of $7.76. Warehousing cost per order is $2.49. The total annual cost for the three-warehouse set-up: $10.25 million.

But if the objective is to have 90% of orders delivered within two days, the calculations show that the e-retailer would require eight warehouses in all, reflecting the need to get closer to the customer (See Figure 1).

Given that more and more e-commerce retailers are starting to offer same-day shipping capability, the company might aim to serve 90% of customers within one day; in that case, it would need a network of 16 or so warehouses.

For a small e-commerce retailer, the capital expense required to build out such a network would be prohibitive. Locking into long-term leases with 3PLs may also be risky, especially if volumes are insufficient to gain economies of scale.

Which brings us to dynamic on-demand warehousing. What if the retailer was able to rent space, using current marketplace rates, for a warehousing network of equivalent size?

We can calculate the costs of the three networks examined above, as well as the latter two networks operated using dynamic on-demand warehousing (see Figure 2).

For dynamic on-demand warehousing, the network structure is the same (that is, warehouses are located in the same places as in the corresponding traditional network).

The immediate difference is that there are no start-up or warehouse leasing costs; the dynamic on-demand network uses marketplace costs for warehouse space, which are only slightly higher per-unit than in a traditional network.

Of course, the relative advantage of the dynamic on-demand network depends on many factors: the actual marketplace rates for warehouse space, demand variability, etc.

As noted earlier, marketplace rates for warehouse space may be greater than, or less than, standard rates with a 3PL. If the warehouse provider has surplus space that will be otherwise unused, it may well offer below-market rates in the short term.

On the other hand, in a high-demand location, marketplace rates are indeed likely to be higher than 3PL rates. With those realities in mind, it’s important to consider demand variability and the effect on dynamic on-demand warehousing.

Test Case 3: Growth scenarios

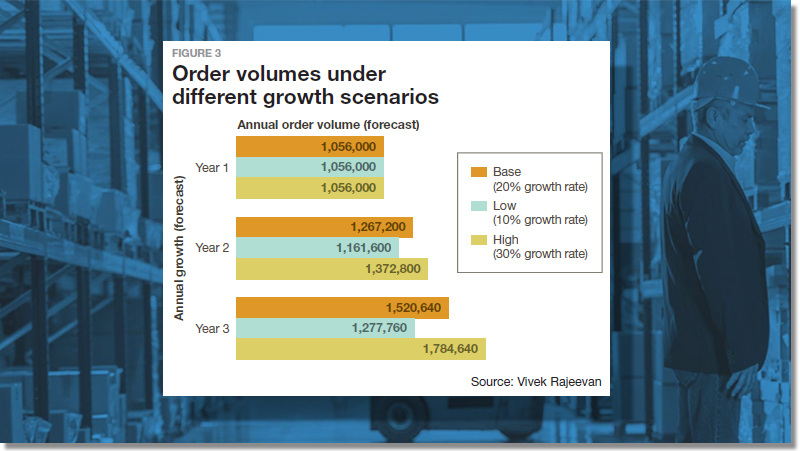

To properly assess the value of dynamic on-demandwarehousing model when demand is uncertain, let’s consider three scenarios in which the e-retailer has annual growth rates of 10%, 20% and 30% respectively. The resulting annual volumes are calculated using the same assumptions and methods cited above (See Figure 3).

To model the traditional system, we assume that the retailer is locking in capacity for three years with sufficient capacity to meet peak demand.

This means that the retailer would lock in sufficient space to meet annual demand of 1,784,640 units, even though utilization would be much lower than that in Year One.

This is conservative; the retailer may well be able to negotiate capacity reservation with the 3PL that does not require so much unused space in that first year.

Nevertheless, for our calculations, we assume that the full capacity is reserved up front.

The cost per order incurred varies as the retailer’s growth rate varies, assuming that it installed capacity sufficient to cope with the high-growth scenario (See Figure 4).

In the leftmost graph, actual annual growth was indeed the 30% that was expected, leading to cost per order of $10.72 and $9.31 for the traditional and dynamic on-demand networks respectively.

The other two graphs show the costs if the actual growth rate was moderate (20%) and low (10%) respectively. In those cases, the costs per order with a traditional network rise to $11.04 and $11.40 respectively, because utilization decreases. Cost per order under the dynamic model, however, stays unchanged at $9.31 because of the pay-per-use nature of the dynamic on-demand warehousing system.

Of course, the retailer may choose to invest assuming a low-growth scenario, and not risk low utilization. In that case, the opposite problem will arise: If actual growth is high, then the retailer runs out of capacity, and risks either losing demand or having to pay other costs to meet the unexpectedly high demand.

This ability to deal with uncertainty is one of the key benefits of dynamic on-demand warehousing. Uncertainty and variability arise in many forms, as we will discuss shortly. It’s important to note that dynamic on-demand warehousing does not present an either-or decision with respect to traditional warehousing.

A retailer may use a blended approach: operating some warehouses, which it owns or contracts with 3PLs, and deploying dynamic on-demand warehousing as a filler when needed. Such a system can offer most of the advantages listed above while also lowering the risk exposure; however, it would require some amount of capital expense.

For many e-commerce players, a mix of approaches may provide optimal levels of costs and service.

Other Pros and Cons of Dynamic On-Demand Warehousing

Dynamic on-demand warehousing also makes it possible to hedge against other types of variability beyond just variations in volume. For instance, it can help address the following:

- Regional variability. Demand could grow much faster in some regions than in others. Dynamic on-demand warehousing provides the ability to increase warehousing capacity in regions with high or fast-growing demand, and decrease warehousing capacity in regions where demand is declining.

- Cost variability. Operating costs can change in different ways across different regions. For instance, tax policies in one state could make costs particularly attractive there, with wage and rent inflation making other regions unattractive. A dynamic on-demand warehousing network can quickly adapt to such changes.

- Supplier variability. As the e-commerce retailer grows, it may add new suppliers in other parts of the country or the world. Or, the supplier itself may add new facilities, or transportation disruptions may cause the flow of imports to arrive through a different port. Again, dynamic on-demand warehousing can quickly adapt to these changing conditions.

It should be mentioned that dynamic on-demand warehousing is not without its own risks. The single biggest risk is that the retailer is exposed to market rates for warehousing space. Putting it in consumer terms: Much like Uber’s surge pricing, market conditions may cause warehousing rates to spike suddenly.

A retailer that has its own network of owned/operated warehouses will typically be in a better position to manage its costs.

Another potential risk factor stems from the fact that orders are being fulfilled by a network of unrelated warehouses contracted only through an online marketplace. As in any such outsourcing situation, operating conditions at some warehouses may not be optimal, leading to errors in order fulfillment, for example, or misalignment with the retailer’s values and objectives.

This risk can be mitigated by appropriate contract structures and monitoring, both on the marketplace platform and via third parties.

Dynamic on-demand warehousing is an idea whose time has come. Not only does it offer a cost efficient way for smaller e-commerce retailers to offer high service levels in a flexible fashion, but it is also likely to become a standard way of contracting for warehousing services.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on Dynamic Warehousing Strategies: On-Demand Warehousing for E-Commerce, by Karl Siebrecht, CEO, FLEXE, Amitabh Sinha, Associate Professor, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, Stephen Johanson, President, Starboard Solutions Corp., and Vivek Rajeevan, Student Consultant, MBA Class of 2017, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, a recent white paper supported by FLEXE.com and Starboard Solutions Corporation and published by the Tauber Institute for Global Operations, 2016. Their support is gratefully acknowledged. Details regarding the network calculations using Starboard Solutions are also available in this white paper.

Related Dynamic On-Demand Warehousing White Papers

Dynamic Warehousing Strategies: On-Demand Warehousing For E-Commerce

There is a strong case that not only does dynamic warehousing offer a cost efficient way for small ecommerce retailers to offer high service levels in a flexible fashion, but it is likely to become a standard way of contracting for warehousing. Download Now!

Chasing Amazon: Building a Dynamic Warehouse Network

Most of Amazon’s competitors are feverishly playing catch-up, and if your company is among them, reassessing your supply chain design, particularly pricing and quick delivery, is a good place to start. Download Now!

Warehouse Capacity Economics and Trends

This paper explores the data and economics behind warehouse capacity and inventory issues, and illustrates how on-demand warehousing can provide a specific, right-sized option when extra space is needed and how to monetize space when it is unused. Download Now!

Article topics

Email Sign Up