The first phase of warehouse robotics may be coming to close. That’s because vendors today are talking more about fulfillment processes, integration, and software rather than the robots.

The types of robotic systems available has matured and diversified. Autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) can assist warehouse associates with picking efficiency. There are also AMRs that move larger loads, autonomous lift trucks, goods-to-person automation, and mobile manipulators. In the past couple of years, rapid progress has been made with pick-and-place systems that use artificial intelligence and articulating robotic arms.

This proliferation of warehouse robotics has come pretty fast and already has brought operational benefits for distribution centers (DCs), but what comes next? While new robots are sure to come, one big change is that more vendors are talking about software capabilities and the imperatives that go with that, like integration and reliable yet flexible process performance.

“We are a fulfillment solution provider, not a robotics vendor,” said Fergal Glynn, vice president of marketing at 6 River Systems, whose Chuck robots work collaboratively with warehouse associates. “The reason being that the robot is a means to an end. What’s important to our customers is the performance of the fulfillment process enabled by the robots.”

Meanwhile, fulfillment centers aren’t just deploying one type of robot. Some are starting to deploy robotics from different vendors, elevating the importance of easy interoperability, said Dwight Klappich, research vice president at analyst firm Gartner Inc.

Application programming interfaces (APIs) from robotics vendors and from warehouse management system (WMS) providers can help. However, things get more complicated when multiple types of robots, fixed automation, and other systems like manifesting or cubing and weighing, need to work in concert.

“The problem is when operations get to the point of deploying heterogeneous fleets of robots, then that API approach becomes increasingly difficult to do,” explained Klappich. “You can end up with all these one-off integrations between multiple systems and a WMS, knowing that every time I want to introduce a new WMS or have a major upgrade, there is this integration effort again. And it’s not just the integration work itself; it’s also about wanting the ability to orchestrate work between robots of different types and with other types of automation.”

Integration and orchestration

The trend toward robots from multiple providers has given rise to a new software niche that Klappich and Gartner called “multirobot orchestration.” These platforms sit between business applications, heterogeneous fleets of robots, and other forms of automation.

The vendors in this emerging category come from different backgrounds, from providers that specialize in integration, to WMS or warehouse execution system (WES) vendors, to robotics suppliers who claim their software is capable of orchestration. This category also involves universal fleet managers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), which offers its RoboMaker product.

The goal of orchestration, explained Klappich, is to more easily establish unified workflows using different robots. For instance, a larger AMR or an autonomous lift truck can bring pallets to replenish a pick area supported by another type of robot. There generally is less need for such a solution if a company is new to robotics, advised Klappich.

“The need depends on the complexity of the environment,” he said. “If you are an operation just getting started with robotics and want to integrate one AMR solution with one WMS, you probably aren’t going to go out and get a multirobot orchestration platform. The need is driven more so by those companies with increasingly heterogeneous fleets.”

6 River Systems has worked with both APIs and integration platforms for deployments, said Glynn. Overall, operations managers want higher-level software that can help them orchestrate processes.

“We will work with partners to integrate disparate technologies together, but we believe that operators are looking for a single unified user experience and control center for their operations,” he said. “We’re already doing this today at some of our customer facilities.”

SVT Robotics SOFTBOT simplifies connections

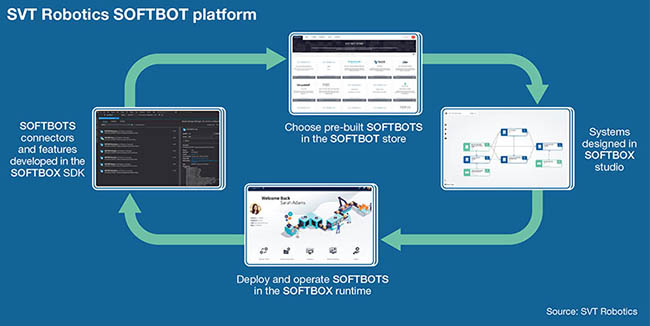

One vendor that specializes in robotics integration is SVT Robotics. The company offers software to simplify the connections between different systems and how they work together on common processes.

SVT’s SOFTBOT platform contains connectors between different robotic systems and enterprise systems like a WMS, and also to other forms of automation such as high-density storage and picking systems, or conveyor systems.

SOFTBOT offers both its own connectors and a drag-and-drop studio function for visually designing integrated process flows. Once designed, which can be done in minutes, the connectors automatically integrate the systems around the designed process without programming, said SVT Robotics.

In addition, the platform offers small apps called SOFTBOT Features to orchestrate how different systems can work in unison, noted A.K. Schultz, co-founder and CEO of SVT Robotics.

But rather than being a full-blown WES, features are “microservices” that do one specific thing. Tasks include parsing incoming orders to determine which system has needed inventory, whether the system is available, and how busy that system is. Using these small apps, the platform can coordinate systems, said Schultz.

“There is integration, and there is orchestration, but what our customers ultimately want is the orchestration,” he said. “They want multiple different systems to be able to work together in concert, to create a new outcome that one system can’t really achieve on its own. But in order to do that, the first step is integration.”

Users look to save time and effort managing AMRs

Consulting firm MacGregor Partners used SOFTBOT to rapidly deploy mobile robots to automate the transport of supplies at a pharmaceutical client's factory. The manufacturing facility needed to maintain a sterile environment, so MacGregor Partners chose AMRs as the transport method. SVT’s platform sped up the integration, and the project also included creation of screens for employees to use to communicate with the AMRs.

An integration platform can help companies cut the time and effort that would otherwise be spent on API-based integration, Schultz said. Rather than need point-to-point integrations to a WMS, SOFTBOT is a common point of integration between automation and a WMS or an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system.

SVT's platform and the connectors are able to “abstract” data integration details into logical information flows, said Schultz. The information includes the location for the next task, what goods need to be transported, and where to drop off goods.

This separates data exchange details from information flows, Schultz said, while letting different systems do what they do best, like fleet management or pick path optimization.

“By creating that abstraction, everybody is free to innovate on the part that they’re focused on, without having to deal with all of this complex, direct coupling of technologies,” said Schultz.

Blue Yonder offers Robotics Hub SaaS

Other vendors are also addressing the need for integration. Supply chain software vendor Blue Yonder's Robotics Hub is aimed at simplifying the integration of multiple types of robots with its WMS.

The software-as-a service (SaaS) offering is intended to streamline integration, not just with the company’s WMS, but also with any upstream system that manages warehouse inventory and orders, said Adam Shawish, product management director for Robotics Hub at Blue Yonder.

“Automation solutions tend to have slightly different ways of communicating [with WMS] so we wanted to standardize those flows with Robotics Hub to reduce the time and effort it takes to roll out and integrate different automation vendors across a warehouse,” he said. “It started out with a focus on [integrating] robotics, but it has since expanded into the onboarding of other types of automation, like goods-to-person systems.”

GreyOrange agents anticipate orders

Multi-agent orchestration is a “core capability” of GreyOrange's GreyMatter software, said Akash Gupta, co-founder and chief technology officer at the robotics vendor. He said GreyMatter's “agents” can coordinate spans, not only its own robots, but also other robots, people, and systems such as automated packaging.

“Agents can work collaboratively or alone, depending on the work process and the task,” Gupta said. “For example, a person might work with a goods-to-person robot, a robotic picking arm, and a mobile conveying robot to pick and pack an order and move it to shipping, or an unmanned intralogistics robot might work independently to move pallets from a dock door to a stock staging area.”

“We believe most companies will prefer to have a mix of agents handling fulfillment, whether in one facility or across their nodes,” he said.

inVia software deployed before hardware

inVia Robotics' software is sometimes deployed before its robots, said Lior Elazary, founder and CEO of inVia. This is done to make human-centered processes more efficient and then make further productivity gains once the robots are deployed, he said.

“More operations are needing this conductor capability to assign work, and decide what agent should do what, and when,” he sid. “Our software can perform this conductor role, and it can be for many types of agents, including people, robots, conveyor systems, other machines or something like an auto bagger.”

Seegrid manages stand-alone and interoperable systems

While robotics vendors should offer effective integration methods, some warehouse operations prefer a stand-alone system, noted Jeff Christensen, vice president of product at Seegrid.

“The ultimate goal is to optimize and improve material flow overall, and integrations between various systems will be a part of this effort,” he said. “Integrations support this effort, but they are not necessarily required to improve mobile automation today.”

Seegrid has customers using integrations to dispatch its Palion AMRs from a WMS or inventory system and some doing it through a pull system or with manual dispatching.

“We also have customers creating integrations with other automation and other vendor’s robots,” Christensen added. “For example, our Palion Tow Tractors are picking and placing at conveyors. Our AMRs can pull alongside the conveyor and transfer an item back and forth between the conveyor and the tow tractor.”

“We also have AMRs currently integrating with roll-up doors in facilities so our robot can open the door as it enters a new space and then close it after it passes through,” he said.

Berkshire Grey works to ensure reliability

When it comes to pick-and-place applications, automation providers say system effectiveness comes as much from AI-based software as it does from the robot arm. Some vendors approach effectiveness and partnerships with integration in mind.

Berkshire Grey typically relies on APIs to integrate with WMS or other systems that govern inventory and orders, according to Kishore Boyalakuntla, vice president of products at the company, which recently released a robotic putwall system.

Not only does Berkshire Grey ensure that its robots work with major WMSes, but it also focuses on the other direction, he said. This bi-directional flow lets a WMS or another system know if a SKU or label was damaged or any item was unable to be processed by the robot.

Even if AI capabilities can deal with variations, partners must consider it a part of integration, Boyalakuntla explained. “We make sure that when we turn on the lights and commission [a system], the pick rates and the throughput are exactly what we agreed upon with the customer or exceed it,” he said.

Honeywell invests in software for smart robots

Pick-and-place automation is very software-driven, using machine learning (ML) smarts to enable the solution to adjust to variations in SKUs or packaging. That means the efficacy of pick-and-place robots in the real world rests heavily on software expertise.

To support this, Honeywell Robotics has invested in software-related “building blocks” for robotics, said Thomas Evans, CTO of the unit of Honeywell Intelligrated.

For example, Honeywell’s Smart Flexible Depalletizer, launched in September, features a robotic arm and AMRs from partners to transport pallets. The robotics control software is from Honeywell, in addition to the company's expertise in AI, ML, and vision.

Honeywell extensively tested the depalletizer system in pilots with customers to ensure that it can perceive and adjust to variations. Evans explained why the company developed its own software controls.

“Our Honeywell Universal Robotic Controller was to be able to have full customization of what we’re providing our customers, which not only enables a quality solution; it also gives us full insight into how to deploy, commission, and maintain that software when it’s in the field,” he said. “And that is very important to us as a solution provider.”

While technologies like machine learning and robotic perception may seem removed from the day-to-day realities at DCs, these building blocks are key to handling the level of variation needed for applications such as depalletizing, especially when sequences of single-SKU pallets and mixed-SKU pallets are run through the system.

“That [flexibility to handle variation] is all within our software control and some of the things we work with the customer on to make sure we handle their pain points with this product,” said Evans.

Covariant aids AI-based robots

AI-based piece picking is still an advanced application for robots, making it difficult end-user organizations to compare them with established categories of materials handling automation, said Ted Stinson, chief operating officer at manipulation AI provider Covariant.

After all, how does one determine if an AI-driven arm and gripper can actually handle the rapidly changing SKU mixes seen in modern e-commerce? Flashy presentations from a dozen or more vendors can’t really answer that question, Stinson said.

“It’s a crowded and confusing marketplace, where trying to understand the capabilities of one system versus another is highly challenging,” Stinson said. “It’s not like some more traditional materials handling system categories, where you can compare specification sheets and pretty well-established metrics around performance.”

One path forward is to run a performance benchmark test and invite vendors to participate. Such tests should involve a mix of five to 25 SKUs and different scenarios for how they might be presented in bins to provide insights on what the systems can really handle.

Typically, such benchmarking gauges things like pick success rate, and the rate at which human intervention is needed. Ultimately, it’s not about comparing robots, but figuring out if AI can help deal with your product mix and fulfillment challenges, Stinson said.

“We encourage benchmarking, because it sets a foundation for an effective partnership by helping a company assess how well a robotics system and the AI that powers it is going to perform when it comes to adapting to its rapidly changing product mix,” said Stinson.

About the Author

Follow Robotics 24/7 on Linkedin

Article topics

Email Sign Up