The demand for picking robots has reached an inflection point. “I’ve never seen so much interest, if not desperation, to improve fulfillment,” said James Lawton, vice president and general manager of robotics automation at Zebra Technologies.

And that’s true for companies as diverse as FedEx and iHerb. They and many others have recently turned to piece-picking automation to solve their fulfillment challenges.

But we're still in the early stages of robotic piece picking. After all, it was only January 2015 when Modern Materials Handling (a sibling of Robotics 24/7) reported on early picking pilots in “The robots are coming – Part I.”

So, supply chain operators would appreciate guidance on best practices in the selection and use of fulfillment systems. There's no cookie-cutter answer for piece-picking robots, even if they look similar to the untrained eye. As Simon Kalouche, founder of Nimble Robotics, put it, “No one wants to automate and lose throughput in the process.”

That may sound silly, but it has happened. We talked to several robotics experts and asked for their advice on success with the latest automated fulfillment systems.

E-commerce, workforce drive automation

“Transformation for robotic automation is picking up speed across traditional and new industries,” said Milton Guerry, president of the International Federation of Robotics (IFR).

Guerry cited e-commerce as a hotbed in particular. “There are thousands of robots installed worldwide today that did not exist in this segment just five years ago,” he said. “Consumer behavior is driving companies to address demand for personalization of both products and delivery.” The others we spoke with concurred.

“More and more companies are realizing the numerous advantages robotics provides their businesses,” Guerry added.

That list of potential benefits ranges from faster, more accurate picking to reduced labor requirements. Both the labor shortage and a lack of interest in working in traditional warehouse settings plays to the value of piece-picking robots.

“New training opportunities with robotics are a win-win strategy for companies and employees alike,” explained Guerry.

Distributors have great expectations for pick-and-place automation.

“This technology is fully capable of producing a high return on investment [ROI] of time, money, and people,” asserted Matt Kohler, director of applications at Bastian Solutions.

“Today, less than 5% of warehouses and distribution centers use piece-picking robots,” said Zebra's Lawton. “Within five years, that will be more than 80%. There will be many companies that will simply go out of business without piece-picking robots.”

Four best practices for robotic picking

Just as applications and benefits of robots have changed, so has the approach of suppliers to distribution centers. Robot vendors used to be enamored of their own technology. However, that approach is shifting. And rapidly.

“Piece-picking robots are all about making the warehouse run better. You don’t want to just buy technology from a bunch of technologists,” said Leif Jentoft, co-founder and chief strategy officer of RightHand Robotics. “It’s not about their love for the technology, but how it helps improve warehouse processes.”

1. Focus on process, not technology

So, here's the first best practice for piece-picking robot success: It’s not about the technology. It is about improving the process.

“Look for a solution that has an impact. It can increase throughput. It can reduce human labor,” said Nimble's Kalouche. “People have to understand their processes first, then work with the supplier on how to improve those processes.”

Lawton added: “Technology vendors have to deliver solutions to problems, not a bucketful of tools.”

That starts with being able to characterize picking processes—manual, automated, batch, wave, goods-to-person, or person-to-goods are some examples.

Furthermore, it’s critical to understand what exactly is involved in the current picking process, said Bastian's Kohler. For instance, beyond simple parts picking, what else do people do? Move totes. Apply labels. Organize orders. Without including all tasks in an appraisal of what the robot will do, the ROI is sure to lag, says Kohler.

2. Robots must meet KPIs

A second best practice: Expect the robots to work to a particular set of key performance indicators (KPIs).

KPIs are all about better fulfillment, said RightHand's Jentoft. There’s the range of inventory that the robots can handle, an expected rate of picking, targeted order integrity, and the expected level of autonomy for the robots.

“Ultimately, it’s about the reliability and accountability of the robots,” he said. “They must enhance the flow and the process.”

Kishore Boyalakuntla, vice president of products at Berkshire Grey, cited FedEx as a company that built its automation to KPIs. The carrier uses robots to handle small packages at several regional hubs.

Ted Dengel, managing director of operations technology and innovation at FedEx, said each robotic system sorts 1,000 to 1,100 packages an hour.

According to Boyalakuntla, FedEx set out to “automatically handle high volumes of small packages in small spaces with limited worker intervention, which significantly reduces labor challenges, streamlines sorting processes, and increases the efficiency of carrier operations.”

That’s a strong set of KPIs, marking several measures of success. It also sets expectations upfront.

3. Systems must be flexible, scalable, modular, and robust

The third best practice is a bit complex. “Look for a system that is flexible, scalable, modular, robust and requires little to no teaching,” said Boyalakuntla. Oh, is that all? But, yes, it is possible, going back to Kohler’s earlier comment about being fully capable. Let’s break it down:

- Flexibility is important because everything keeps changing from SKUs to order profiles. What a robot picks today may not be the same for long.

- Scalability is important because throughput is changing. Remember how different e-commerce looked before COVID-19.

- Modular is important because it allows the easiest path to adapting to dynamic conditions.

- Robust is important because it accommodates the first four requirements on the list.

- Requires little to no teaching is important because this is the future that is already here. Suppliers generally agree that artificial intelligence advances that allow robots to learn on the fly are the single greatest technical advancement of the past couple of years.

4. Integration over point solutions

We’ll round this out with a fourth best practice: The best solution is an integrated one, not a point solution. No one can afford to have an island of automation in a dynamic, fast-paced facility.

This can be accomplished in a couple of different ways. One is to integrate it directly to the warehouse management system (WMS) and other facility-wide software systems.

“A second approach is to have robots function autonomously, similar to the ways that humans work,” said Jonathan Styles, director of continuous improvement at iHerb. “This pushes real-time data collection and decision making to the edge of what is currently possible using AI.”

That’s the path Styles chose for the Nimble robots that interface with a bank of automated sorting equipment.

Stationary versus mobile piece picking

At this point, there are two distinct approaches to piece-picking robots.

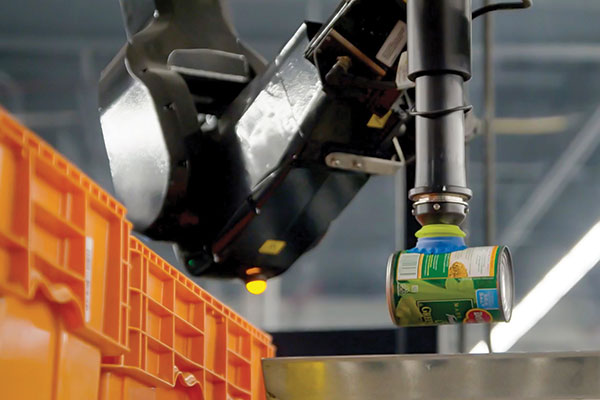

One is what you would expect. A robot with a single arm, vision system, AI, and related software. There’s also the end effector that is either a suction cup or gripper with fingers of some configuration. The majority of these are stationary, but they can be made mobile by mounting them on a vehicle of some sort. Many operate outside of a cage.

The other approach is the one taken by Zebra. It recently bought Fetch Robotics, a supplier of autonomous mobile robots (AMRs). As Lawton explained, Zebra's AMRs are not outfitted with robotic arms. Instead, people manually pick items and place them on the robot, which carries them through a pick path, collecting other items and on to a final destination.

The idea is to reduce—if not eliminate—steps and travel time of the people out on the floor, said Lawton. He called it a “zone-based, robot-assisted solution that optimizes the behavior of robots and people.” And Lawton didn’t rule out the possibility of a robotic arm on each AMR a few years from now.

There’s no question that robots are all about removing as much human labor from piece picking as possible. And while Zebra does that in one way, applications that use robotic arms require people in another.

Quite simply, piece-picking robots with arms are not entirely autonomous. A bank of them requires people to intervene occasionally when they can’t solve a problem. These range from deciding what to do when an empty bin arrives, but the robot is supposed to pick two items to the wrong items are in a bin.

Autonomy and process

Exactly how autonomous a robot should be is up for discussion. While some cite lower numbers, Bastian's Kohler put it at 98% to 99%.

Percentages aside, probably the best gauge is how many people are needed to manage so many robots. If two robots have a problem every minute or two that requires different staffing than for a bank of 20 robots that each have a problem every 30 minutes or so. Ultimately, it’s all about the process.

If you’re looking for some final advice for piece picking robot success, RightHand's Jentoft said, “Don’t let technology eclipse the importance of making the warehouse run better.”

About the Author

Follow Robotics 24/7 on Linkedin

Article topics

Email Sign Up