Manufacturing is changing. Never mind the remarkable utility of 3D scanning, the customization capability of additive manufacturing, or the facile methods of rapid prototyping—there’s a whole new way of using cloud computing to disseminate design information instantly. Potentially, it provides a new chapter in the way we manufacture everything. Welcome to contract manufacturing—also known as manufacturing as a service (MaaS).

“For decades now, companies have shifted from vertically integrated design, engineering and manufacturing, to relying on external contract manufacturing partners,” says Andrew Edman, industry manager for product design, engineering, and manufacturing at Formlabs in Somerville, Mass.

“Even manufacturers that continue to be highly vertically integrated depend on external vendors for components that go into their finished goods,” he adds. “Outsourcing production, whether via traditional manufacturing methods, or more cutting-edge practices like on-demand 3D printing, frees up organizations to focus more on their core competencies and less on the complexities of dealing with the literal nuts and bolts of manufacturing.”

Borrowed processes

This shift in focus has already made inroads in other industry verticals. Curt Heverly is the managing director of Open Doors Consulting in Glendale, CA. He likens the MaaS evolution to that of other industries, such as plastics injection molding, where the concept is successful.

“Injection molding output [IMO] is sold as a service, instead of purchasing an injection molding press, auxiliary equipment and robotics,” he says. “All traditional equipment purchases require technical support and trained employees to optimize processes for each unique project. Current financial and timing hurdles must be overcome in the competitive race to get products quicker to market.”

Heverly says IMO is the plastic industry’s take on a share economy. OEM suppliers are selling moldable hours or pounds.

“A complete documented process that is plug and play for the newly laid out plastic plants of the next millennium. You are purchasing a block of plastic processing output tailored for the current projects in the facility,” Heverly says. “Speed to market and shorter product life cycles require nimble and flexible equipment financing arrangements. Lack of labor, technical and non-technical, requires an automated solution. Building blocks of automation must be able to be assembled and repositioned as product and project mix accelerates in every quickening consumer demand velocity.”

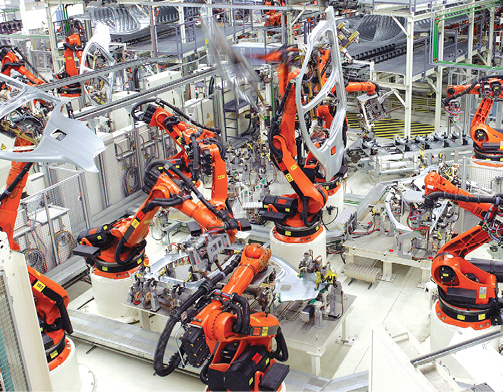

Having available—and ready—assets is the goal of many robotics firms. The robotics industry is aware of the trend and is preparing to meet the demand of contract manufacturing. Joe Gemma, chief robotics officer at KUKA Robotics explains that the company is putting the right tools in place.

“We have engaged with other companies on a ‘pay per use’ basis to help manage capital expenditures, while providing manufacturing flexibility,” he says. “Other companies are providing this type of service like Vicarious on the West Coast, as an example, and many others are beginning to enter this space. We see this change in manufacturing philosophy taking hold, but it may not be widespread in all industries, particularly with low volume and high mix portfolio products.”

Bright horizon

Although KUKA isn’t fully preparing for cloud-based manufacturing orders, most firms are orienting their business models to the cloud. The future of contract manufacturing is accelerated by other “as a service” functionalities emerging in the cloud.

“I would say the great initial benefit has been centered on networking and the low overhead of communicating to solicit bids and efficiently identify capable suppliers,” says Dr. Stephen J. Rock, senior research scientist and additive manufacturing lab director at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Center for Automation Technologies and Systems in Troy, NY.

Rock says that as more complex manufacturing operations are contemplated for outsourcing, distributed processing via the cloud is an opportunity. According to Rock, the cloud enables the rapid access of “simulations that might support automated quoting of higher complexity parts or assemblies, assists in cross-organization production scheduling, or perhaps enables value-added design optimization suggestions based on the particular manufacturing capacity available at any moment in time.”

“The computational and networking capabilities of the cloud may also support sophisticated material modeling that relies on multi-organization expertise across the design and manufacturing spectrum,” he says. “Longer term, manufacturers can also benefit by leveraging cloud computing concepts and applying them directly to manufacturing operations.

“Distributed manufacturing may allow a job to be easily divided between several facilities for faster turn-around or cost optimization,” Rock adds. “Networking efficiency can enable load shifting between a wide array of solution providers. The resilience afforded by independence from any single point of failure should help suppliers and their customers sleep well at night.”

Of course, even if the move to the cloud takes time, organizations are already seeing the effects of MaaS. “Manufacturing as a service is changing the way engineers work,” says Alkaios Bournias Varotsis, Ph.D., technical marketing engineer at Hubs in Amsterdam.

Varotsis says that online manufacturing will change the world on a similar scale as the introduction of the shipping container, which enabled a truly global manufacturing ecosystem.

“Online manufacturing will have the opposite effect,” Varotsis explains. “By combining the connectivity of the cloud with the advantages of digital manufacturing technologies, like 3D printing and [computer numerical control] CNC machining, production will turn again local, eliminating altogether the need for transportation and storage and significantly reducing the waste and the environmental impact of manufacturing.”

Manufacturing limits?

As good as it sounds, MaaS may not be the panacea. It has limits.

“The limiting factor is all about the assembly of parts with different materials and processes—which is not yet possible with instant cloud quote services,” explains Marco Perry, founder of Brooklyn-based product design firm Pensa. “Such projects need conversations, expertise and contracts. If that is available in the future, it will change the market.”

Another limiting factor may be the availability of skill sets to meet the potential upward demand that contracted and MaaS may impose. Although it widens the market of vendors to a worldwide scope, the skills still may not always be available where you need them, when you need them.

“The limiting factors to this shift include an unwillingness to change, reluctance to embracing new technology, inability to learn and adapt new technological processes of manufacturing and, finally, an unskilled workforce that can’t use the technology,” says David Armendariz an executive recruiter with the technical division of the Lucas Group.

MaaS: Manufacturing lightning?

MaaS could become lightning in a bottle for a whole new world of product expectations, driven by a digital fabric, a super-agile supply chain and a crowd of end users who want parts as fast as possible.

Perry points out that since the industrial revolution, manufacturing companies have sold and mass-produced products that are the same design. That was then. This is now, though.

“The problem with that model is that people don’t want exactly the same product,” says Perry. “Today, more companies than ever are able to market to niche audiences—with a small production volume—because cloud fabrication is now possible. And for the future, it’s the holy grail for companies to use cloud manufacturing to produce complete products.”

About the Author

Follow Robotics 24/7 on Linkedin

Article topics

Email Sign Up