So here we are. Time for some pretty brutal truths.

Brexit may well turn out to be a terrible idea. But if Britain is going to survive and have any hope of prospering, whomever winds up running the country is going to have to take that on the chin – whether they supported “leave” or not – and start moving quickly. That is going to be tough.

Within the UK government, no one has planned for this outcome. Inside the offices of Whitehall, UK officials were explicitly prohibited from considering responses to a Brexit. Britain now urgently needs a strategy for engaging with the world outside the structures of the European Union. And it doesn’t have one.

Exactly how the following days and weeks will play out is far from clear. David Cameron says he wants to stay in office until October. That may not yet be a foregone conclusion.

All we know for sure, to be honest, is that the British people have made their decision and that they – by the slimmest of majorities – want out of the European Union. What exactly will replace it, if anything, is much, much less clear.

The results show the country savagely, bitterly divided. Essentially, voters in London and Scotland voted to remain within the EU by a very substantial margin. Pretty much everyone else voted to leave. Already, speculation Scotland might quit the United Kingdom is rising – although what that really means will not be apparent for some time to come. If anything, the country now feels even more polarized than it did the day before the vote. Tying it back together is vital – but that will take time and effort.

What has just happened will be a psychological blow to both elected politicians and civil service and foreign office officials. Some had already privately said they might quit in the event of a “leave” vote rather than oversee a policy they believed would see the UK’s global influence nosedive.

Hopefully, that won’t happen. The UK needs a whole host of new policies on a wide variety of fronts. Even assuming it decides to quit the EU now, under the terms of the Lisbon treaty it still has two years of membership to run. Beyond that, however, it will need an entire new immigration system built almost from scratch as well as a multiple renegotiated trade deals – if it can get them.

Providing some clarity on that may be key to stopping the local and global market hemorrhage. More broadly, however, Britain needs to somehow outline a path to ongoing global relevance given that its voters have just gone against the advice of pretty much every major world leader.

That’s not necessarily impossible. Britain’s political elite might be reeling but there remains a broad internationalist consensus, even amongst many of those who lobbied for Brexit. The UK remains one of the premier economic and military powers in Europe. It is still a member of NATO.

Earmarking more troops to support NATO allies in Eastern Europe, for example, would send a strong signal that the UK remained committed to the defense of the continent even as it moves to disentangle itself from the EU.

Maintaining a relatively open immigration policy would also send a similarly strong signal that the UK will remain internationalist. With Britain out of the EU, that could include a rather more liberal visa regime for migrants from the United States, Australia and New Zealand. That may not be politically easy, given just how great a motivating factor migration concerns were in bringing out the “leave” vote.

For many European and other migrants in the United Kingdom, last night’s fight will feel like a kick in the teeth. This morning, even some pro-“remain” Britons are talking about leaving. Somehow they will need to be reassured that the country they thought they knew is not about to change out of all recognition.

None of that will stop the short-term economic pain and political instability. If the margin of victory had been more significant, the UK might have been better able to put its recent period of political divisions behind it. The result is so close, however, that recrimination and regret seems all but inevitable.

How the UK’s major partners will react will not be immediately clear. In many ways, it’s in everyone’s interest for the exit from the EU to be relatively amicable and simple. But Washington, Paris and Berlin all have their own other preoccupations.

Still, by voting to leave the UK electorate have gone some way to addressing what many in the country clearly felt was a serious democratic deficit. On immigration in particular, the lack of control UK voters felt they had over their borders was clearly a source of considerable anger and frustration. That can, theoretically at least, now be addressed.

Britain has now set a precedent within Europe, however, that could usher in events more disruptive than its own EU exit. Electorates in Greece, Spain and elsewhere are at least as frustrated about austerity as UK voters were on migration. Many in Germany and elsewhere feel that way about the repeated bailouts of troubled Mediterranean nations. And the refugee crisis has hardly gone away, even if the number of arrivals has dropped substantially in 2016.

In some respects, once it has disentangled itself from the EU, the United Kingdom now has more freedom of maneuver than at any point in its recent history. Whether the pain it will feel in the short term leaves that feeling with it, however, is another matter entirely. Right now, there is an awful lot to play for – and very, very little looks certain.

Source: Reuters

UK: A Divided Nation

by Martin Armstrong

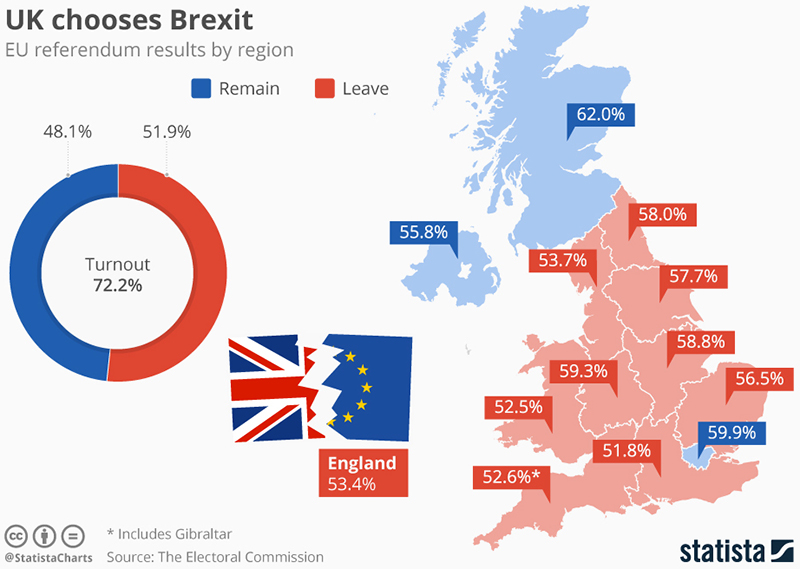

And so the people spoke. As the results trickled in during the night it gradually became clear that the UK was heading towards Brexit. Flying in the face of the majority of experts and academics, the public chose to leave the European Union. To be precise - 51.9 percent chose to leave.

For the other 48.1 percent and indeed the rest of the world, the shock is still resonating. No one, on either side, knows what is going to happen – economically, politically or socially. Prime Minister Cameron has resigned, the pound has fallen to the lowest level for over 30 years, and an initial 120 billion pounds has been wiped off the FTSE 100.

The close nature of the result highlights a stark split in the will of the population, not just from person to person but, perhaps more significantly, from country to country. Not a single area in Scotland voted to leave the EU with a total of 62 percent voting against the proposed Brexit. This has inevitably led to calls for a second referendum on Scottish independence. Having narrowly voted against independence from the UK in 2014, the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, has said another vote is ‘highly likely’.

Today’s result might not just pull the United Kingdom out of the European Union, it may well end up tearing this divided nation apart.

Regional breakdown of the United Kingdom EU referendum results

Related Article: Brexit EU Referendum Impact Yet To Be Measured By U.S. Logistics Managers

Article topics

Email Sign Up