The plummeting price of oil is still the biggest energy story in the world.

It’s bringing back cheap gasoline to the United States while wreaking havoc on oil-producing countries like Russia and Venezuela.

But why does the price of oil keep falling?

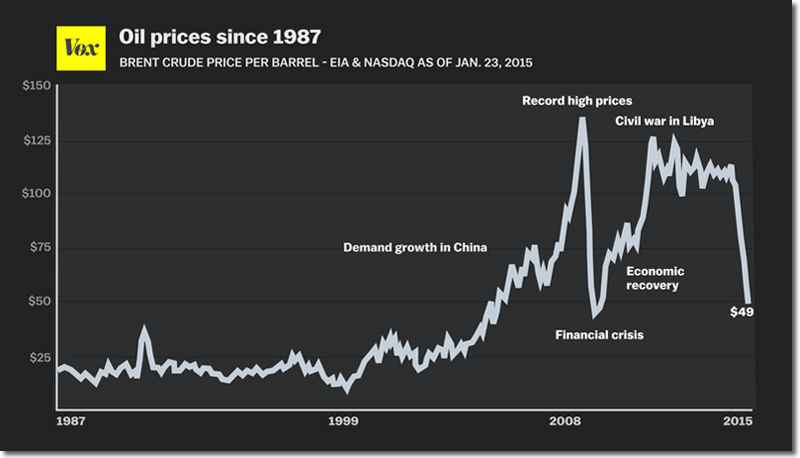

Back in June 2014, the price of Brent crude was up around $115 per barrel. As of January 23, 2015, it had fallen by more than half, down to $49 per barrel.

The short version of the story goes like this:

For much of the past decade, oil prices have been high - bouncing around $100 per barrel since 2010 - because of soaring oil consumption in countries like China and conflicts in key oil nations like Iraq.

Oil production in conventional fields couldn’t keep up with demand, so prices spiked.

Spot price of Brent Crude, updated on January 23, 2015 (Joss Fong/Vox)

But beneath the surface, many of those dynamics were rapidly shifting.

High prices spurred companies in the US and Canada to start drilling for new, hard-to-extract crude in North Dakota’s shale formations and Alberta’s oil sands.

Then, over the last year, demand for oil in places like Europe, Asia, and the US began tapering off, thanks to weakening economies and new efficiency measures.

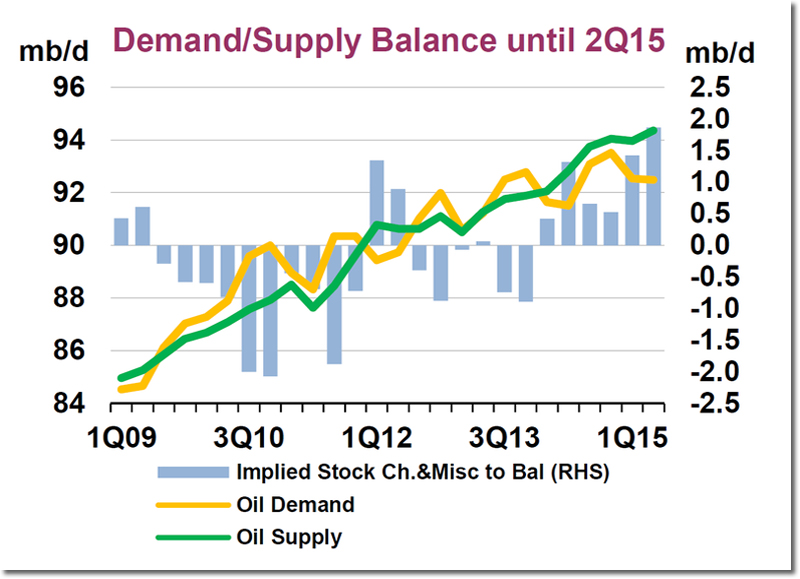

By late 2014, world oil supply was on track to rise much higher than actual demand, as the chart below from the International Energy Agency shows. A lot of unused oil was simply being stockpiled away for later. So, in September, prices started falling sharply.

(International Energy Agency)

As prices slid, many observers waited to see whether OPEC, the world’s largest oil cartel, would cut back on production to push prices back up. (Many OPEC states, like Saudi Arabia and Iran, need higher prices to balance their budgets.) But at its big meeting last November, OPEC did nothing. Saudi Arabia didn’t want to give up market share and refused to cut production - in the hopes that lower prices would help throttle the US shale boom. That was a surprise. So oil went into free-fall.

The oil price crash is now upending the global economy, with ramifications for every country in the world. Low prices are excellent news for oil consumers in places like Japan or the US, where gasoline is the cheapest it’s been in years. But it’s a different story for nations reliant on oil sales. Russia’s economy is facing a potential meltdown. Venezuela is facing unrest and may default on its debt. Even better-prepared countries like Saudi Arabia could face heavy pressure if oil prices stay low.

Why Oil Prices Plummeted in 2014

To understand this story, we first have to go back to the mid-2000s. Oil prices were rising sharply because global demand was surging - especially in China - and there simply wasn’t enough oil production to keep up. That led to large price spikes, and oil hovered around $100 per barrel between 2011 and 2014.

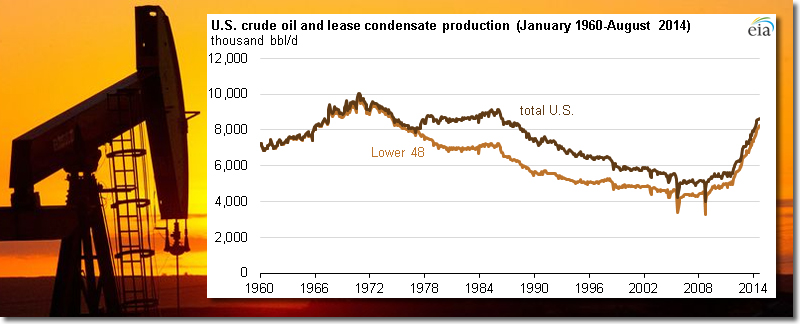

Yet as oil prices increased, many energy companies found it profitable to begin extracting oil from difficult-to-drill places. In the United States, companies began using techniques like fracking and horizontal drilling to extract oil from shale formations in North Dakota and Texas. In Canada, companies were heating Alberta’s gooey oil sands with steam to extract usable crude.

This led to a boom in “unconventional” oil production. The US alone has added 4 million extra barrels of crude oil per day to the global market since 2008. (Global crude production is about 75 million barrels per day, so this is significant.)

(International Energy Agency)

Up until very recently, however, that US oil boom had surprisingly little effect on global prices. That’s because, at the exact same time, geopolitical conflicts were flaring up in key oil regions. There was a civil war in Libya. Iraq was facing threats from ISIS. The US and EU slapped oil sanctions on Iran and pinched its oil exports. Those conflicts took more than 3 million barrels per day off the market:

(US Energy Information Administration)

By mid-2014, however, those outages and conflicts were no longer quite as important. Production in the United States and Canada was still rising fast - and the world’s supply of oil kept growing.

Even more significantly, oil demand in Asia and Europe suddenly began weakening - thanks to slowdowns in China and Germany. More broadly, oil demand has been flatlining in lots of places around the world. The United States, once the world’s biggest oil consumer, has seen gasoline consumption stagnate as cars became more fuel efficient. At the same time, countries like Indonesia and Iran have been cutting back on subsidies for fuel users.

That combination of weaker-than-expected demand and steadily rising supply caused oil prices to start dropping from their June peak of $115 per barrel down to around $80 per barrel by mid-November. And that was only the start…

OPEC’s Surprising Response: Let Prices Keep Falling

That brings us to OPEC, a collection of oil-producing nations that pumps out about 40 percent of the world’s oil. In the past, this cartel has sometimes tried to influence the price of oil by coordinating either to cut back or boost production.

At its big meeting in Vienna on November 27, there was a lot of heated debate among OPEC members about how best to respond to the drop in oil prices. Some countries, like Venezuela and Iran, wanted the cartel (mainly Saudi Arabia) to cut back on production in order to prop up the price. These countries need high prices in order to “break even” on their budgets and pay for all the government spending they’ve racked up:

OPEC “break-even” prices in 2012. (Matthew Hulbert/European Energy Review)

On the other side of the debate was Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest crude oil producer, which was opposed to cutting production and seemed willing to let prices keep dropping.

Why was that? For one, officials in Saudi Arabia remember what happened in the 1980s, when prices fell and the country tried to cut back on production to prop them up. The result was that prices kept declining anyway and Saudi Arabia simply lost market share. What’s more, the Saudis have signaled that they can live with lower prices in the short term. (The government has built up $750 billion in foreign-exchange reserves to finance deficits.)

In the end, OPEC couldn’t quite agree on a response and ended up keeping production unchanged. “We will produce 30 million barrels a day for the next 6 months, and we will watch to see how the market behaves,” said OPEC Secretary-General Abdalla El-Badri after the meeting.

That caused the price of oil to start crashing even further. The price of Brent crude went from $80 per barrel to $70 per barrel in just a few days. And it kept tumbling to down below $60 per barrel by mid-December and $50 by January.

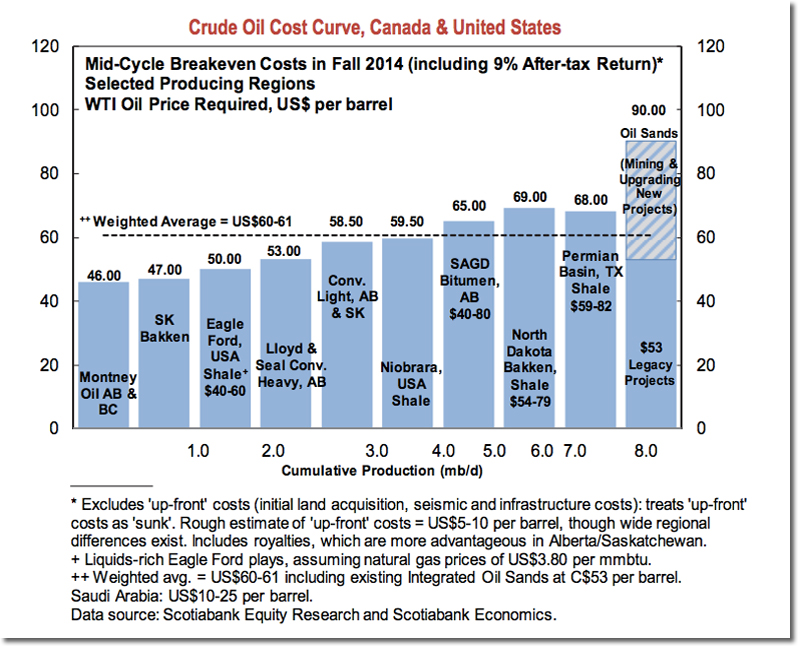

For all intents and purposes, OPEC is now engaged in a “price war” with the US. What that means is that it’s relatively cheap to pump oil out of places like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. But it’s more expensive to extract oil from shale formations in places like Texas and North Dakota. So as the price of oil keeps falling, some US producers may become unprofitable and go out of business. And the price of oil will stabilize. At least that’s what OPEC members hope.

A Big Question: Will Low Oil Prices Kill The US Shale Boom?

By January 2015, it was clear that low prices were starting to pinch producers in the United States and Canada. The only real question is how much it would hurt.

Analysts often focus on a metric called the “breakeven price” for oil-drilling projects - the price of oil necessary for a project to produce reasonable returns. ScotiaBank has estimated breakeven prices for various shale and oil sands projects across North America:

(ScotiaBank)

US shale projects are especially vulnerable when oil dips below $60 per barrel. Fracking wells tend to deplete quickly - with output falling about 65 percent after the first year - so new wells have to be drilled constantly. So, when the price falls, many companies can respond quickly by scaling back on new drilling. Already, firms are pulling out of places like Texas’ Permian Basin, and the number of US rigs has fallen 15 percent from December to January.

But not everyone is leaving all at once: Some companies have sunk costs and need to keep drilling. Others may try to cut their costs and grit it out. It really varies from company to company. What’s more, the situation is different up in Canada: oil sands projects have huge upfront costs, but once those are paid off, they can keep producing oil cheaply for many decades.

That all makes it hard to predict how this all shakes out - or where global oil prices will bottom out. The US Energy Information Administration still expects that overall US oil production will grow another 700,000 barrels per day in 2015 - though that’s slightly lower than the prediction when prices were high. We’re about to see if that’s right.

How Falling Oil Prices Could Affect Russia, Iran, and the US

The plunge in oil prices is having significant economic consequences around the world. A few examples:

Russia: Russia’s situation is getting the most attention these days. The country’s is hugely dependent on oil and gas production - with oil revenues making up 45 percent of the government budget - and the sharp fall on prices has been ruinous.

Economists now estimate that Russia’s GDP will shrink at least 4.5 percent in 2015 if oil says below $60 per barrel. The plunging price of oil has also caused the ruble’s value to collapse - which is leading to panic inside Russia and a rise in inflation, as imports become drastically more expensive. Many Russians, worried that their savings may vanish, have been rushing out to buy cars and washing machines - anything that has more lasting value than currency.

So far, Russia’s central bank has been struggling to deal with this crisis. On December 15, 2014, the country suddenly hiked interest rates from 10.5 percent to 17 percent in an attempt to stop people from selling off rubles. But those rate hikes are likely to slow the country’s economy down even further.

Iran: Iran’s economy had recently started to rebound after years of recession. The International Monetary Fund had been projecting that the country was on track to grow 2.3 percent next year. But that was all before oil prices started to plunge - a potentially precarious situation for the country.

One big problem for Iran is that it also needs oil prices well north of $100 per barrel to balance its budget, especially since Western sanctions have made it much harder to export crude. If oil prices keep falling, the Iranian government may need to make up revenues elsewhere - say, by paring back domestic fuel subsidies (always an unpopular move, at least in the short term).

Venezuela: There’s growing concern that the oil crash could cause Venezuela, another major oil producer, to default. The nation’s economy - heavily dependent on oil revenue - is set to shrink some 3 percent this year and inflation is rampant.

Saudi Arabia: There’s no question that Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest crude producer (after Russia), will suffer financially from cheap oil. If oil stays at around $60 per barrel next year, the government will run a deficit equal to 14 percent of GDP.

For now, however, the Saudis are toughing this out - and show no sign of trying to prop up prices as they have in the past. The kingdom has built up a stockpile of foreign currency worth some $750 billion, which it will use to finance its deficits. In December, the country’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, said he didn’t care if prices crashed to $20 or $40 per barrel, he wasn’t going to budge from his position. “It is not in the interest of OPEC producers to cut their production, whatever the price is,” he said.

That said, if low oil prices persist, Saudi Arabia may have to cut back on some of the social programs it had instituted after the Arab Spring. And Naimi’s strategy of maintaining oil output is controversial within the kingdom. (In January 2015, Saudi King Abdullah died, but his successor Salman said he would maintain the current oil policy.)

The United States: In the US, meanwhile, a fall in crude prices will have both positive and negative impacts. For many people, it will offer an excellent economic boost: cheaper oil means lower gasoline prices - which have fallen to $2.04 per gallon, the lowest since 2009:

(GasBuddy.com)

The EIA projects that US drivers will spend about $550 less on gasoline in 2015 than they did in 2014, assuming prices stay low. That will give consumers more money to spend on other things.

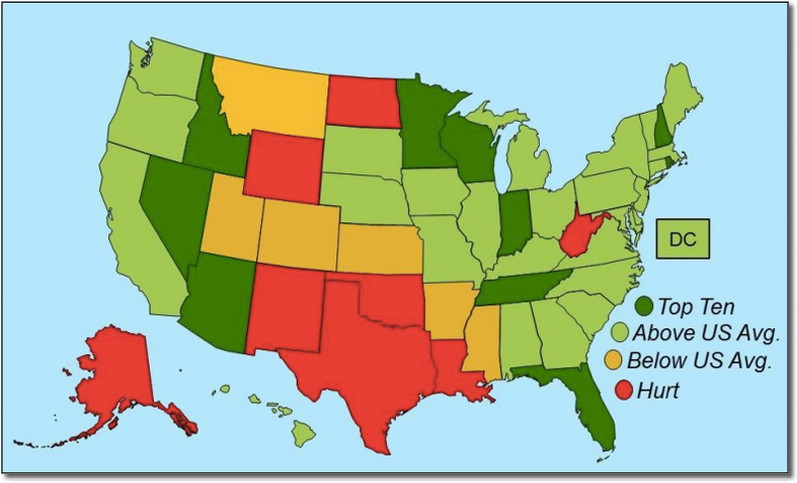

But it’s not all good news. Oil-producing states like Texas and North Dakota are likely to see a drop in revenues and economic activity. The falling price of oil is also putting severe pressure on Alaska’s state budget. All told, oil prices are likely to be good for 42 states (in green) and bad for the other 8 (in red):

Figure 3. Lower Oil Prices Will Boost Economic Activity in 42 States

Source: Based on Brown Yücel (2013)

(Resources for the Future)

If the price drop lasts a long time, that could also spur people to start using more oil. Case in point: In recent years, high gasoline prices have spurred many Americans to buy smaller, more efficient cars. But if gasoline prices fall, bigger cars and SUVs could make a comeback. (That said, overall US fuel economy will still keep rising over time - because the federal government has imposed new standards on cars and light trucks through 2025. But this might now happen more slowly.)

For more on the impacts on oil use, see: “Driving in the US has been declining for years. Will cheap gas change that?”

Will Global Oil Prices Stay Low?

This is very hard to predict. If oil demand remains weak and production stays high, prices might not bounce back for some time.

But the world is full of potential surprises. Conflict could break out again in Libya or Iraq, which would hamper oil production. China’s economy could come roaring back. Europe could suddenly rebound out of its malaise. Saudi Arabia could decide that enough is enough and cut back on production all of the sudden. Any of those things could increase prices.

So far, we haven’t seen any of those shocks. In fact, all the surprises have gone the other way - in January, both Iraq and Russia announced that they were exporting more oil than ever, and prices slumped even further.

If history is any indication, oil prices will eventually rise again, though it could take some time. And some experts think we should be preparing for that day. In the Financial Times, energy expert Michael Levi wrote a piece on how the US (and other countries) could take advantage of low oil prices to make needed energy-policy reforms - such as ending wasteful fossil-fuel subsidies or putting in place new efficiency measures. That would help countries insulate against future price shocks.

But that’s hardly guaranteed to happen: Many policymakers might just decide low oil prices are here to stay and use it as an excuse to cut back on efficiency measures or energy alternatives.

Source: Vox

Related: Sand in the Oil of the Supply Chain

Article topics

Email Sign Up